SEOUL, South Korea: Researchers in Seoul have mapped embryonic dental cells that appear pre-programmed either to build the tooth itself or to form its supporting tissues. The work adds detail to a fragmented picture of how the embryonic mouth is pre-wired and, while it will not immediately change clinical practice, it refines the blueprint that future tooth-regeneration and bioengineered replacement strategies will need to follow.

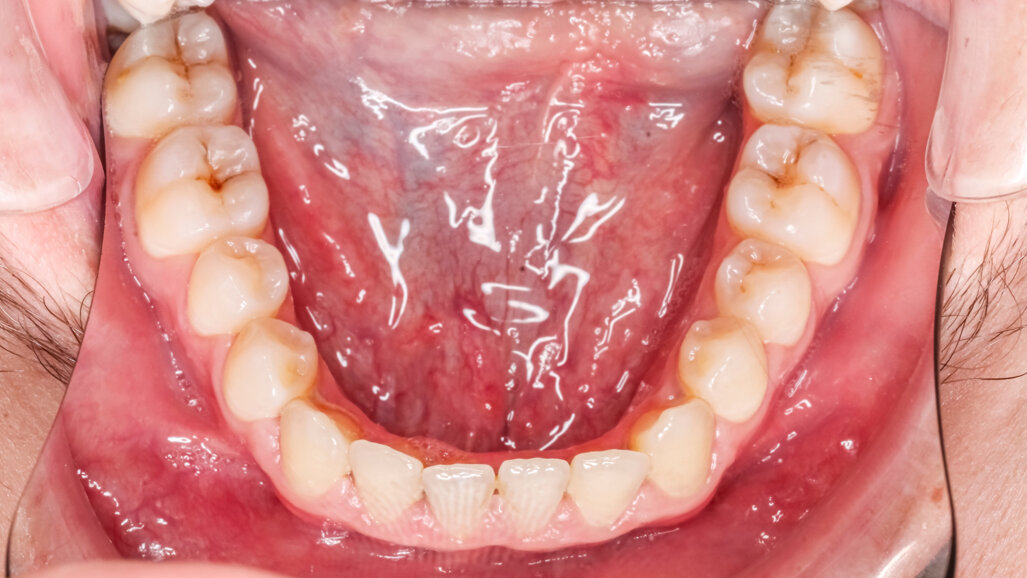

In classical embryology, a tooth germ progresses from bud to cap to bell before it lays down roots and erupts into the mouth. During these stages, a surface epithelial layer interacts with deeper mesenchymal tissue, which ultimately gives rise to dentine, pulp and much of the supporting apparatus. Cells interpret so-called positional information—gradients of signalling molecules that tell them where they are and what they should become. The new study, led by scientists at Yonsei University College of Dentistry, set out to understand how this positional coding works specifically along the lingual–buccal axis of developing molars by comparing these two sides of tooth germs.

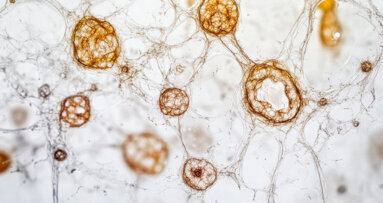

The team investigated the first mandibular molar germs at the cap stage, taken from mice. They split each germ in the mesio-distal direction and isolated the dental mesenchyme on the lingual and buccal sides. They then performed bulk RNA sequencing on each half—essentially determining which genes were active in each population—and repeated related analyses at the bell stage. Gene ontology analysis showed that lingual mesenchymal cells were enriched for programmes related to odontogenesis, tissue patterning and hard tissue formation, whereas buccal mesenchyme showed more activity in pathways linked to mesenchymal and neural crest development, stemness, regeneration and growth.

Lingual mesenchyme builds the tooth proper

To test whether these molecular differences translated into different outcomes, the researchers recombined either lingual or buccal mesenchyme with dental epithelium and transplanted the constructs under the kidney capsule of mice, an established in vivo niche for tooth-germ culture.

Only recombinants that contained lingual mesenchyme formed organised tooth structures with odontoblasts, ameloblasts and calcified tooth tissue. Constructs based solely on buccal mesenchyme failed to generate a complete tooth and instead produced mainly surrounding, bone-like and periodontal-type tissues. In reaggregation experiments, dissociated lingual and buccal mesenchymal cells were mixed, allowed to reassemble into aggregates and then combined with epithelium. Remarkably, the mixed cells sorted themselves into distinct territories and again contributed differentially: lingual-derived cells populated dentine and pulp, whereas buccal-derived cells contributed primarily to alveolar bone and periodontal ligament.

Dr Eun-Jung Kim, first author of the study, commented in an article in the British Dental Journal: “We were curious to know if they could find their original place and reorganise when the fluorescently labelled lingual and buccal mesenchymal cells were mixed randomly, which they not only did, but the lingual cells grew into dentine to form the tooth as before. This phenomenon is called cellular self-organisation.”

This behaviour, the authors argued, reflects that the dental mesenchyme is prespecified: cells retain a memory of their original position and act on it, even when displaced.

R-spondins and the WNT/BMP balance

The group then asked how these positional differences are controlled at the signalling level. They focused on major developmental pathways, particularly WNT and BMP, which act as key regulators of proliferation, differentiation and tissue patterning.

Comparative pathway analysis highlighted members of the R-spondin (RSPO) family—notably RSPO1, RSPO2 and RSPO4—as being upregulated in lingual mesenchyme after short-term culture, alongside WNT-related odontogenic genes. In contrast, buccal mesenchyme showed stronger BMP-associated activity and upregulation of BMP inhibitors, consistent with a shift towards bone and surrounding tissue formation.

Functional assays reinforced this picture: in a chemotaxis setup, lingual mesenchymal cells migrated towards RSPO1-conditioned medium, whereas buccal cells preferentially moved towards Noggin, a BMP pathway antagonist. Overall, the authors propose that a WNT-boosted, RSPO-rich environment favours tooth-forming behaviour in lingual mesenchyme, while a BMP-biased context on the buccal side promotes the formation of bone and periodontal structures.

Summarising their work, the authors conclude that their data provides “novel insights into the molecular basis of positional information in tooth development and pattern formation”.

Implications for tooth engineering

Taken together, the findings suggest that having dental stem cells is not sufficient; what matters is which mesenchymal population those cells resemble and what positional signals they receive. For future tooth engineering, the study suggests several design principles:

1. Choose the right mesenchymal compartment. A lingual-like mesenchymal profile seems necessary to generate a tooth germ capable of making dentine and pulp, whereas buccal-type cells are better suited to building supporting tissues.

2. Recreate positional cues. Tooth-forming regions may require R-spondin/WNT-type activity, while periodontal or bone targets may need a different mix of BMP-weighted signals.

3. Respect spatial layout. Even at the cap stage, lingual and buccal cells are not interchangeable; mixing them without regard to their positional identity risks losing tooth-forming potential.

For clinicians, the work does not change any current protocols; however, it reinforces a trend. As developmental biology fills in the map of how a tooth is assembled, the long-term prospect of biologically based tooth repair or replacement becomes less science fiction and more a question of learning how to recreate the right cells in the right place at the right time.

The study, titled “Prespecified dental mesenchymal cells for the making of a tooth”, was published on 9 October 2025 in the International Journal of Oral Science.

Topics:

Tags:

ROCHESTER, N.Y., US: In what is thought to be the first study to directly link prenatal stress hormones with primary tooth eruption, researchers in the US ...

As dental professionals, we have all had that gut-wrenching moment when a cancer patient walks through our door mid-treatment. Their mouths are full of ...

FORT LAUDERDALE, Fla., US: Swiss dental implant specialist Patent Medical has been named “Dental Implants Manufacturer of the Year in Europe” by MedTech...

In recent years, dental implants have emerged as a pivotal advancement in dentistry, offering a popular solution for replacing natural teeth lost owing to ...

PHILADELPHIA, US: Periodontal disease affects nearly 60% of adults over the age of 65 and imposes a considerable burden—medically, psychologically and ...

LONDON, England: Previous research has shown that, when combined, dental epithelial and mesenchymal cells can form tooth-like structures in vitro called ...

SINGAPORE: Gingival tissue grafting is a well-established procedure in periodontal therapy; however, conventional techniques are often associated with ...

TAIPEI, Taiwan: Conventional periodontal therapies, while effective to a degree, often fall short of fully restoring the complex architecture and function ...

Live webinar

Wed. 25 February 2026

11:00 am EST (New York)

Prof. Dr. Daniel Edelhoff

Live webinar

Wed. 25 February 2026

1:00 pm EST (New York)

Live webinar

Wed. 25 February 2026

8:00 pm EST (New York)

Live webinar

Tue. 3 March 2026

11:00 am EST (New York)

Dr. Omar Lugo Cirujano Maxilofacial

Live webinar

Tue. 3 March 2026

8:00 pm EST (New York)

Dr. Vasiliki Maseli DDS, MS, EdM

Live webinar

Wed. 4 March 2026

12:00 pm EST (New York)

Munther Sulieman LDS RCS (Eng) BDS (Lond) MSc PhD

Live webinar

Wed. 4 March 2026

1:00 pm EST (New York)

Austria / Österreich

Austria / Österreich

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bulgaria / България

Bulgaria / България

Croatia / Hrvatska

Croatia / Hrvatska

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

France / France

France / France

Germany / Deutschland

Germany / Deutschland

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Hungary / Hungary

Hungary / Hungary

Italy / Italia

Italy / Italia

Netherlands / Nederland

Netherlands / Nederland

Nordic / Nordic

Nordic / Nordic

Poland / Polska

Poland / Polska

Portugal / Portugal

Portugal / Portugal

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Slovenia / Slovenija

Slovenia / Slovenija

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Spain / España

Spain / España

Switzerland / Schweiz

Switzerland / Schweiz

Turkey / Türkiye

Turkey / Türkiye

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

Brazil / Brasil

Brazil / Brasil

Canada / Canada

Canada / Canada

Latin America / Latinoamérica

Latin America / Latinoamérica

USA / USA

USA / USA

China / 中国

China / 中国

India / भारत गणराज्य

India / भारत गणराज्य

Pakistan / Pākistān

Pakistan / Pākistān

Vietnam / Việt Nam

Vietnam / Việt Nam

ASEAN / ASEAN

ASEAN / ASEAN

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Middle East / Middle East

Middle East / Middle East

To post a reply please login or register