Worldwide, 60–90% of schoolchildren and nearly 100% of adults have dental caries, making untreated tooth decay the most common oral condition.[1,2] Caries and periodontal disease share many risk factors with non-communicable diseases, including tobacco use, high sugar intake and lack of exercise.[3] Therefore, behavioural changes are needed to decrease the risk of developing these diseases. For caries specifically, the frequency and amount of sucrose consumption should be reduced.[4] This improvement in dietary habits would be beneficial to general health as well.

In some cases, such as studies on food intake, body weight maintenance, glycaemic response, serum lipid profiles, blood pressure and the effects of sucrose-containing medication, sucrose or sucrose-containing products are still used as a comparator in clinical studies [reviewed in 5,6]. In dental caries-related randomised clinical trials, the use of sucrose as a comparator can be considered unethical, as the correlation between sucrose consumption and caries incidence is well established. Consequently, many of the studies investigating the association between sucrose consumption and caries are cross-sectional or population studies. To date, there are few non-randomised interventions and cohort studies that have evaluated this. A recent meta-analysis on studies from as early as the 1950s found that collectively these studies showed that oral health outcomes improved as sucrose consumption was reduced.[4] Diet and nutrition can affect tooth de- and remineralisation in both protective and destructive ways. Frequent consumption of fermentable carbohydrates increases acid production and favours aciduric bacteria and thus caries development, but a healthy diet, low in added sucrose and high in calcium, fluoride and phosphate, can benefit mineralisation.[7]

Therefore, in addition to clinical trials evaluating the cariogenicity of foods using comparators other than sucrose, different ways of estimating the cariogenicity of foods or food ingredients are needed. These include animal trials, enamel slab experiments, plaque pH evaluation and laboratory methods.[8] Animal, mostly rat, caries experiments provide the means to control diet or single food ingredients carefully.[9]

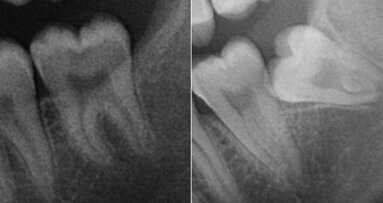

Animal studies have been used to evaluate frequency and amount of sucrose consumption, starch and milk cariogenicity, and frequency of fruit consumption in relation to caries [10]. If possible, it is suggested that animal trials should be combined with plaque pH or intra-oral methods to gain more information.[8] Intra-oral or enamel slab models utilise appliances with real or modelled enamel or dentine that are kept in the oral cavity by volunteers. Periodically, the appliances are placed in experimental solutions, and then caries development related factors are measured.[9] The benefits of enamel slab experiments include the presence of saliva, oral microbiota and mastication, in addition to test products. The cariogenicity of foods like cheese, starch and cookies has been evaluated using enamel slab methods.[8] The plaque pH method, which is a means of following the pH of the plaque during and after eating, is another useful tool for evaluating acidogenicity of food items.[9] It should be noted that acidogenicity is not equal to cariogenicity, as foods or food ingredients may also have possible protective factors.[10]

In addition to all the above-mentioned methods, laboratory models of varying degrees of complexity exist. In these models, depending on the research question, there may be no bacteria present or they may be pure culture studies or multispecies models or use salivary microbes in the model. These models cannot evaluate caries development per se, but factors that increase the risk of caries, including demineralisation, acid production, oral pathogen growth and microbial dysbiosis.

Studies on determining the cariogenicity of foods and food ingredients are limited. Most research has focused on sucrose, various sucrose-containing products, starch and alternative sweeteners, such as polyols. Evaluations of dairy products and fruits have been performed too.[10] Among the polyols, xylitol has received interest since the 1970s when the Turku sugar studies were performed.[11] Xylitol is used widely as a sugar substitute. It is not metabolised by mutans streptococci, thus substituting sucrose with xylitol reduces the substrate for acid-producing oral bacteria and in the long term leads to caries prevention.[12, 13] Xylitol increases salivary flow like other sweet products do.[14,15] It has other beneficial effects on oral health, including the decrease of plaque acidogenicity[16, 17] and the reduction of the amount of plaque.[13,18,19] Xylitol is able to inhibit the growth of several bacterial species, especially Streptococcus mutans,[20-22] without disturbing the commensal oral microbiota.[23,24] The European food safety authorities have recognised this and chewing gum with 100% xylitol as a sweetener has a health claim of reducing caries in children.

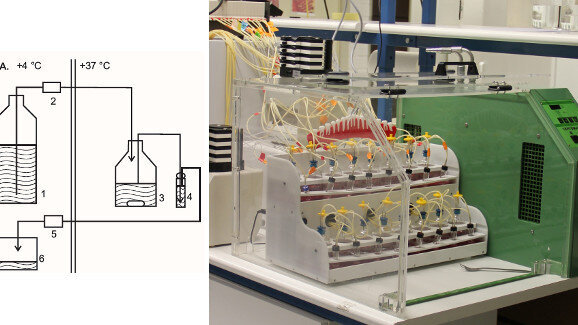

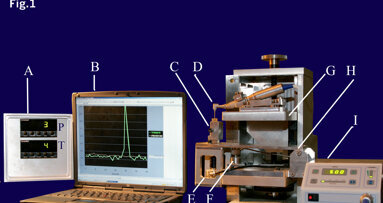

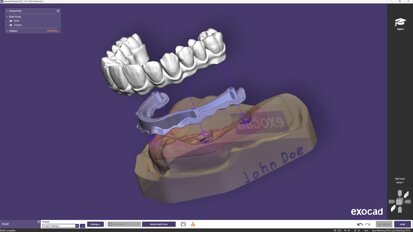

In order to ethically and reproducibly study the effects of xylitol and its mechanisms of action in comparison with sucrose, in vitro models are indispensable tools. Our team has developed an in vitro model of the oral cavity with constant temperature and mixing, using a constant-flow artificial saliva as medium and hydroxyapatite-coated discs in whole human saliva as artificial teeth (Figs. 1a & b).[25-28] We have used this dental simulator to successfully investigate the effect of sucrose and xylitol on growth and adhesion of S. mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus.[27] This model can be used to evaluate planktonic bacterial growth and bacterial attachment of different bacteria on the artificial tooth surface. The results obtained thus far suggest that with this model it is possible to simulate the effects of sucrose and xylitol on the tested bacteria as previously observed in clinical trials. Sucrose increased the amount of all four tested planktonic and adhered S. mutans and S. sobrinus strains. Xylitol, however, decreased all but one of the tested strains.[26]

Of course, the short-term in vitro evaluations described above cannot show direct effect on caries, a multifactorial disease that develops slowly. Nevertheless, effects on the amount of planktonic bacterial species that have been clearly connected to caries and to the risk of maternal transfer of mutans streptococci to the infant are valuable.[29-31] Furthermore, reducing the amount of attached or adhered bacteria can translate to less dental plaque with fewer harmful bacteria and in this manner reduce the acidogenic burden and prevent enamel dissolution.

Recently, I presented our newest findings at the FDI Annual World Dental Congress in Poznań in Poland. The model appears to be suitable for testing the influence of confectionary and confectionary ingredients on the colonisation of mutans streptococci and may thus be useful in the development of tooth-friendly products.

Editorial note: A list of references is available from the publisher.

Swiss oral health company CURADEN has launched CURAPROX Perio Plus at IDS 2019. This pioneering antiseptic range is chlorhexidine, but not as you know ...

Nowadays, implant-supported prostheses are used more and more in people’s daily routines and removable prostheses in case of large rehabilitation ...

With the continuous introductions of endodontic rotary files, recommended techniques for their use seem to proliferate even more rapidly. Although a desired...

Objective: The objectives of the study were to evaluate the correlation between the degree of surgical difficulty measured by an established scale and the ...

BRISBANE, Australia: An unhealthy diet can be a contributing factor to poor oral and general health, and advertising plays a key role in this regard. ...

ROME, Italy: World Food Day is celebrated annually on 16 October, marking the day the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), a United Nations agency, was...

MUNICH, Germany: Many food components contribute directly to the characteristic taste of food and beverages by means of their own particular taste, scent or...

As the global conversation around oral health continues to evolve, the European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) is playing an increasingly influential ...

As the scientific programme director of the Chinese Stomatological Association (CSA) for the 2025 FDI World Dental Congress (FDIWDC25), Prof. Tianmin Xu ...

LONDON, England: Driven by the NHS dental crisis, an increasing number of UK patients seeking cheaper dental work overseas are encountering unexpected ...

2024 has been a busy and exciting time for the digital dentistry industry, so many new products having been released every three to four weeks this year. ...

Live webinar

Wed. 4 March 2026

12:00 pm EST (New York)

Munther Sulieman LDS RCS (Eng) BDS (Lond) MSc PhD

Live webinar

Wed. 4 March 2026

1:00 pm EST (New York)

Live webinar

Wed. 4 March 2026

8:30 pm EST (New York)

Lancette VanGuilder BS, RDH, PHEDH, CEAS, FADHA

Live webinar

Fri. 6 March 2026

3:00 am EST (New York)

Live webinar

Mon. 9 March 2026

12:30 pm EST (New York)

Live webinar

Mon. 9 March 2026

3:00 pm EST (New York)

Live webinar

Tue. 10 March 2026

4:00 am EST (New York)

Assoc. Prof. Aaron Davis, Prof. Sarah Baker

Austria / Österreich

Austria / Österreich

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bulgaria / България

Bulgaria / България

Croatia / Hrvatska

Croatia / Hrvatska

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

France / France

France / France

Germany / Deutschland

Germany / Deutschland

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Hungary / Hungary

Hungary / Hungary

Italy / Italia

Italy / Italia

Netherlands / Nederland

Netherlands / Nederland

Nordic / Nordic

Nordic / Nordic

Poland / Polska

Poland / Polska

Portugal / Portugal

Portugal / Portugal

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Slovenia / Slovenija

Slovenia / Slovenija

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Spain / España

Spain / España

Switzerland / Schweiz

Switzerland / Schweiz

Turkey / Türkiye

Turkey / Türkiye

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

Brazil / Brasil

Brazil / Brasil

Canada / Canada

Canada / Canada

Latin America / Latinoamérica

Latin America / Latinoamérica

USA / USA

USA / USA

China / 中国

China / 中国

India / भारत गणराज्य

India / भारत गणराज्य

Pakistan / Pākistān

Pakistan / Pākistān

Vietnam / Việt Nam

Vietnam / Việt Nam

ASEAN / ASEAN

ASEAN / ASEAN

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Middle East / Middle East

Middle East / Middle East

To post a reply please login or register