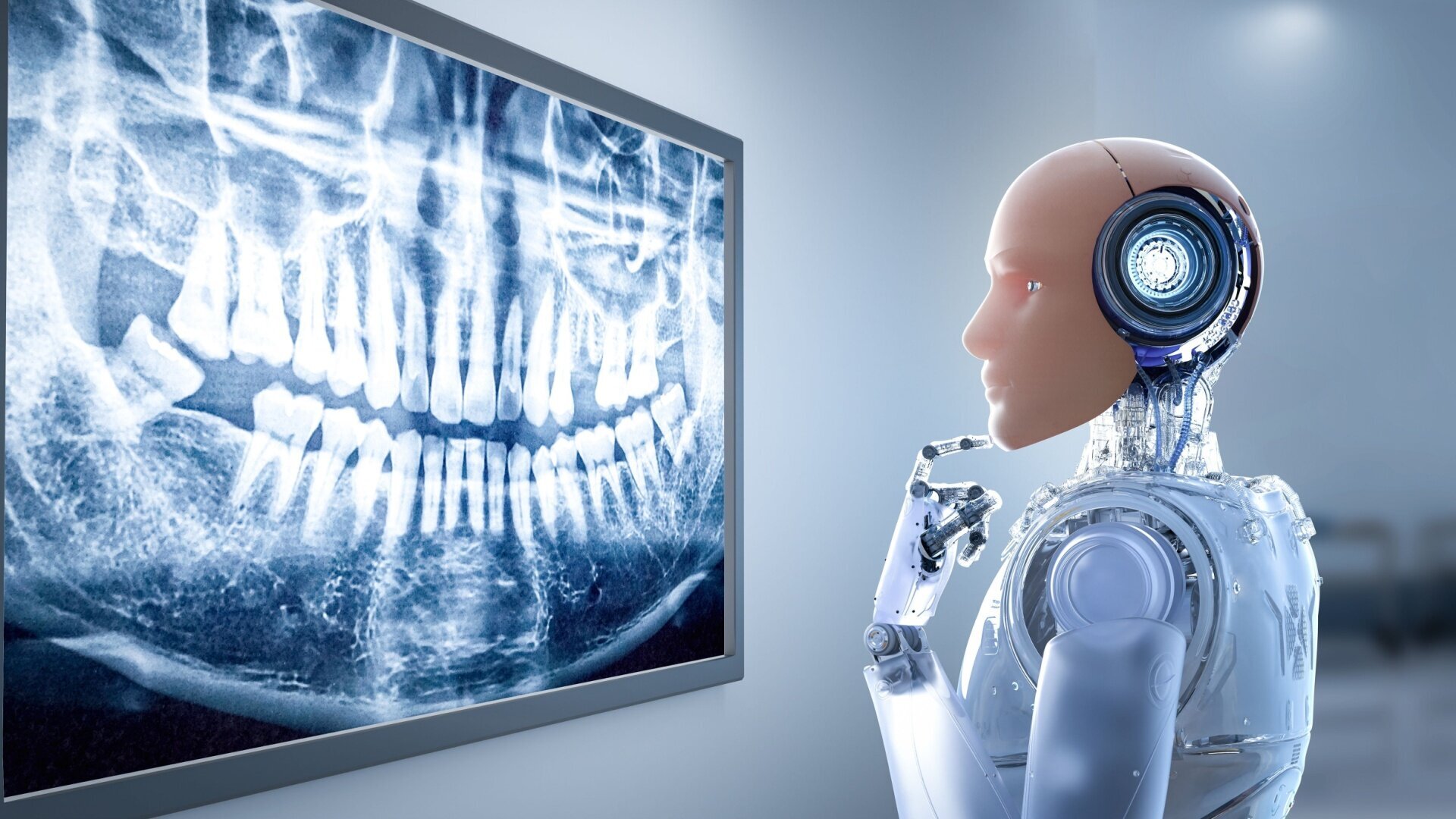

For dental professionals themselves, there are an array of hazards that must be studiously negotiated. Genge continued, “Dentists, eager to stay competitive, may sometimes embrace AI without fully understanding its limitations or ensuring compliance with existing laws. Some lack adequate training to use AI effectively or critically evaluate its output. In some cases, reliance on marketing claims about AI’s capabilities has overshadowed rigorous assessment. There is a gap in ensuring all AI systems meet compliance standards and ethical guidelines.”

These views are echoed by Gaudin, who states that “since the AI algorithms do not perform with a 100% accuracy, the dentist may rely too much on the AI which, for example, may lead to a caries treatment that is actually not there. This diagnostic imperative remains solely in the hands of the dental assistant and the dentist.”

A final and crucial dilemma that problematises the swift uptake of AI is data security and the potential of sensitive patient information to be appropriated and exploited by cyber-attacks, another core focus of Genge’s ongoing work. “Dental practices handle sensitive patient data, making them targets for cyber-attacks. If AI tools are poorly secured, or staff are not trained on what data can and cannot be used in different applications, patient records could be compromised. Additionally, cybercriminals are now leveraging AI which means that more than ever we need to ensure dental teams are receiving proper security awareness training, and that practices have a multi-layered approach to network and system cybersecurity.”

Without question, the inclusion of AI within dentistry is generating extensive transformations and its adoption remains a mixed blessing. Its ability to perform a wide sweep of technical and administrative tasks rapidly, accurately and economically is clearly its principal attraction. However, as this article has shown, both the technology and its human operators are imperfect creations, similarly prone to err. Like the wider economic system of which it is a part, there may be no way of arresting its incessant diffusion, but at the very least, we must ensure that, through rigorous training, regulation and ethical frameworks, its potential for harm is reduced to the bare minimum.

Austria / Österreich

Austria / Österreich

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bulgaria / България

Bulgaria / България

Croatia / Hrvatska

Croatia / Hrvatska

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

France / France

France / France

Germany / Deutschland

Germany / Deutschland

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Hungary / Hungary

Hungary / Hungary

Italy / Italia

Italy / Italia

Netherlands / Nederland

Netherlands / Nederland

Nordic / Nordic

Nordic / Nordic

Poland / Polska

Poland / Polska

Portugal / Portugal

Portugal / Portugal

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Slovenia / Slovenija

Slovenia / Slovenija

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Spain / España

Spain / España

Switzerland / Schweiz

Switzerland / Schweiz

Turkey / Türkiye

Turkey / Türkiye

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

Brazil / Brasil

Brazil / Brasil

Canada / Canada

Canada / Canada

Latin America / Latinoamérica

Latin America / Latinoamérica

USA / USA

USA / USA

China / 中国

China / 中国

India / भारत गणराज्य

India / भारत गणराज्य

Pakistan / Pākistān

Pakistan / Pākistān

Vietnam / Việt Nam

Vietnam / Việt Nam

ASEAN / ASEAN

ASEAN / ASEAN

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Middle East / Middle East

Middle East / Middle East

To post a reply please login or register