Undoubtedly, digital dentistry is the current topic. Over the last five years, the entire digital workflow has progressed in leaps and bounds. There are so many different digital applications that it is sometimes difficult to keep up with all the advances. Many dentists are excited about the advantages of new technologies, but there are an equal number who doubt that the improved clinical workflow justifies the expense.

I have many times heard the argument that there is no need to try to fix something that is not broken. It is so true that impressions have their place and there are certainly limitations to the digital workflow that anyone using the technology should be aware of. For me, however, the benefits of digital far outweigh the disadvantages. In fact, the disadvantages are the same as with conventional techniques.

Chairside CAD/CAM single-visit restorations have been possible for over 20 years, but it was only recently that we became able to mill chairside implant crown restorations after the release of Variobase (Straumann) and similar abutments. I made my first CEREC crown (Dentsply Sirona) back in 2003 with a powdered scanner, and the difference from what I remember then to how we can make IPS e.max stained and glazed restorations (Ivoclar Vivadent) now is amazing.

An investment not an expense

The results of a survey regarding the use of CAD/ CAM technology were published online in the British Dental Journal on 18 November 2016. Over a thousand dentists were approached online to take part in the survey and the 385 who replied gave very interesting responses. The majority did not use CAD/CAM technology, and the main barriers were initial cost and a lack of perceived advantage over conventional methods.

Thirty per cent of the respondents reported being concerned about the quality of the chairside CAD/CAM restorations. This is a valid point. We must not let ourselves lose focus that our aim should always be to provide the best level of dentistry possible. For me, digital dentistry is not about a quick fix; it is about raising our performance and improving predictability levels by reducing human error.

In the survey, 89 per cent also said they believed CAD/CAM technology had a major role to play in the future of dentistry. I really cannot imagine that once a dentist has begun using digital processes that he or she would revert to conventional techniques.

What is digital implant dentistry?

Many implant clinicians have probably been using CAD/CAM workflows without even realising it, as many laboratories were early adopters, substituting the lost-wax technique and the expense of gold for fully customised cobalt–chromium milled abutments (Fig. 1).

One of my most important goals in seeking to be a successful implantologist is to provide a dental implant solution that is durable. We have seen a massive rise in the incident of peri-implantitis and have found that a large proportion of these cases can be attributed to cement inclusion from poorly designed cement-retained restorations (Fig. 2). Even well designed fully customised abutments and crowns can have cement inclusion if the restoration is not carefully fitted (Fig. 3). This has led to a massive rise in retrievability of implant restorations, with screw-retained crowns and bridges now being the goal. However, making screw-retained prostheses places even greater emphasis on treatment planning and correct implant angulation.

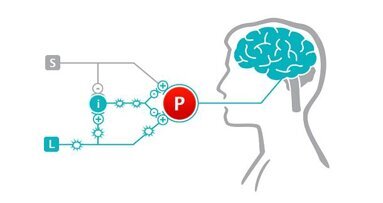

With laboratories as early adopters, we have been milling titanium or zirconia customised abutments for over ten years (Fig. 4). What has changed recently in the digital revolution is the rise of the intraoral scanner. We now have a workflow in which we can take a preoperative intraoral scan and combine this with a CT scan using coDiagnostiX (Dental Wings) in order to plan an implant placement accurately and safely. We can also create a surgical guide to aid in accurate implant placement, have a temporary crown prefabricated for the planned implant position and then take a final scan of the precise implant position for the final prosthesis.

Accuracy of intraoral scanners

Figures 4 to13 show the workflow for preoperative scanning, which includes the implant design, guide fabrication and surgical placement of two fixtures. Intraoral scanners have improved over the last few years, and their accuracy and speed provide a viable alternative to conventional impression taking. The digital scan image comes up in real time and you can evaluate your preparation and quality of the scan on the screen immediately. Seeing the preparation blown up in size no doubt improves the technical quality of your tooth preparations. The scan can then be sent directly to the laboratory for processing.

While we do not think of intraoral scanners as being any more accurate than good-quality conventional impressions, there are many benefits of scanning, such as no more postage to be paid for impressions, vastly reduced cost of impression materials, almost zero re-impression rates and absolute predictability.

Of course, there are steep learning curves with the techniques, but once a clinician has learnt the workflow, there really is no looking back.

We have three different scanners in the practice: the iTero (Align Technology), the CEREC Omnicam (Dentsply Sirona) and the Straumann CARES Intraoral Scanner (Dental Wings; Fig. 14). The CEREC Omnicam is fantastic for simple chairside CAD/CAM restorations, such as IPS e.max all-ceramic restorations on Variobase abutments. For truly aesthetic results, we, of course, still have a very close working relationship with our laboratory, but, undoubtedly, patients love the option of restoration in a day. Being able to scan an implant abutment and then an hour later (to allow for staining and glazing) fitting the definitive restoration is a game changer. Patients also love watching the production process as they see their tooth being milled from an IPS e.max block.

Figures 15–19 show the production process, including the exposure of the implant, the abutment seating, the scan flag on top of the abutment, the healing abutment during fabrication and the delivery of the final prosthesis. However, for more than single units or aesthetic single-unit cases, we use the iTero and Straumann scanners. The latter we have only had at our disposal since February. While it is a powdered system at the moment, this is due to change this month. Particularly with implant restorations, the need to apply a scanning powder is a limitation, owing to a lack of moisture control contaminating the powder. The technology, however, is superb, as is the openness of the system, which provides the advantage of being able to export files into planning software. A colleague of mine even uses it for his orthodontic cases now instead of wet impressions.

We invested in the iTero scanner five years ago and have used it for everything, from simple conventional crowns and bridges to scanning for full-mouth rehabilitations. When fabricating definitive bridgework, we use Createch Medical frameworks for screw-retained CAD/CAM-milled titanium and cobalt–chromium frameworks. Even though intraoral scanning appears extremely reproducible and accurate, I still use verification jigs where needed to ensure our frameworks are as accurate as possible. There are many intricacies that we consider and tips and techniques that we employ to make the scans more accurate that we have developed over time. The closer the scanbodies are together, the more accurate the scan is. Also, the more anatomical detail, such as palatal rugae or mucosal folds, the better the scans can be stitched together.

Figure 20 shows a CBCT volume to aid in planning for mandibular implant placement (Fig. 21) and realising the implant placement. We exposed the fixtures and placed Straumann Mono Scanbodies (Fig. 22). Then, we took an iTero scan of the fixtures in situ (Fig. 23) and made a verification jig from this (Fig. 24) to ensure passive implant positioning. The iTero models were made (Fig. 25) and a Createch titanium framework was used to support porcelain in a screw-retained design (Fig. 26). The last two figures show the excellent outcome and accurate framework seating (Figs. 27 & 28).

Choosing your workflow

There are many different systems on the market now, each offering a one-stop shop. If you are considering investing in a digital scanner, then take some advice from colleagues. One of the most important things is to ensure the system you opt for is an open one that allows you to extract the digital impression data into different software. We extract our files into CT planning software, model production software, chairside milling for stents, temporaries and definitive restorations, and now orthodontic planning software. I am convinced there will be yet more advances with time. The size of the camera is critical—some can be very cumbersome—and it is worth asking the salesperson what developments are underway.

Some companies are more on the cutting edge than others. My favourite at the moment is the Straumann scanner. Its design is light and user-friendly and it synchronises perfectly with implant planning software coDiagnostiX. Furthermore, while it offers a chairside milling unit, it also synchronises perfectly with my laboratory for larger cases.

To conclude, digital implant dentistry is the future and so why not take advantage of it and help improve your clinical outcomes?

Editorial note: A list of references is available from the publisher. This article was published in CAD/CAM - international magazine of digital dentistry No. 03/2017.

Milestone Scientific offers basically one single product in the dental field: the STA Single Tooth Anesthesia System. The instrument replaces a syringe for ...

MADRID, Spain: With change comes opportunity—this is true also for the orthodontic business, which is changing rapidly owing to altering patient demands ...

My dear readers, be cordially welcomed again to the series “Successful communication in your daily practice”. I am Dr Anna Maria Yiannikos, and I am in ...

COPENHAGEN, Denmark: As the realm of digital dentistry continues to evolve, offering unprecedented opportunities for enhanced patient care and practice ...

There are many benefits to refurbishing or relocating your dental practice, and although the decision to make such major physical changes is usually ...

Every dentist is looking to grow his or her practice, and we are all looking to bring in as many new patients as we can. Numerous excellent articles have ...

Imagine getting to your clinic every day and feeling confident that whatever happens to you, you will be able to resolve it. Resolve a problem easily—in a...

I know this subject is scary and most of you don’t even want to think about producing video as part of your Internet marketing program. It’s ...

PIEŠT’ANY, Slovakia: Reliable, robust and compact to cater to dental practices with limited space—this is Model One 200, the latest dental chair unit...

Video is the most powerful Internet marketing tool available today to market your practice. With the rise of YouTube and other video sites, any size ...

Live webinar

Tue. 24 February 2026

1:00 pm EST (New York)

Prof. Dr. Markus B. Hürzeler

Live webinar

Tue. 24 February 2026

3:00 pm EST (New York)

Prof. Dr. Marcel A. Wainwright DDS, PhD

Live webinar

Wed. 25 February 2026

11:00 am EST (New York)

Prof. Dr. Daniel Edelhoff

Live webinar

Wed. 25 February 2026

1:00 pm EST (New York)

Live webinar

Wed. 25 February 2026

8:00 pm EST (New York)

Live webinar

Tue. 3 March 2026

11:00 am EST (New York)

Dr. Omar Lugo Cirujano Maxilofacial

Live webinar

Tue. 3 March 2026

8:00 pm EST (New York)

Dr. Vasiliki Maseli DDS, MS, EdM

Austria / Österreich

Austria / Österreich

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bulgaria / България

Bulgaria / България

Croatia / Hrvatska

Croatia / Hrvatska

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

France / France

France / France

Germany / Deutschland

Germany / Deutschland

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Hungary / Hungary

Hungary / Hungary

Italy / Italia

Italy / Italia

Netherlands / Nederland

Netherlands / Nederland

Nordic / Nordic

Nordic / Nordic

Poland / Polska

Poland / Polska

Portugal / Portugal

Portugal / Portugal

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Slovenia / Slovenija

Slovenia / Slovenija

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Spain / España

Spain / España

Switzerland / Schweiz

Switzerland / Schweiz

Turkey / Türkiye

Turkey / Türkiye

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

Brazil / Brasil

Brazil / Brasil

Canada / Canada

Canada / Canada

Latin America / Latinoamérica

Latin America / Latinoamérica

USA / USA

USA / USA

China / 中国

China / 中国

India / भारत गणराज्य

India / भारत गणराज्य

Pakistan / Pākistān

Pakistan / Pākistān

Vietnam / Việt Nam

Vietnam / Việt Nam

ASEAN / ASEAN

ASEAN / ASEAN

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Middle East / Middle East

Middle East / Middle East

To post a reply please login or register