However, these fabrication methods are time-consuming, and a large portion of the work is performed by the dental laboratory. The large number of appointments required and low reimbursement by statutory health insurance place further strain on dental practices. Through the ongoing digitalisation in dentistry, new treatment options are emerging for this patient group. The digital workflow employed in the following case report provides insight into the treatment of edentulous patients.

Clinical case presentation

A 74-year-old female patient presented to our outpatient dental clinic after a recent serial extraction in the maxilla and mandible that left only teeth #11 and 21. A prosthetic treatment plan was not available. Teeth #11 and 21 were deemed non-restorable owing to advanced bone loss and mobility (Grade III). Owing to incomplete ossification and soft-tissue wound healing as well as the necessity of extracting teeth #11 and 21, we decided to fabricate provisional dentures with 3D printing. These were to be replaced by definitive milled dentures once the hard- and soft-tissue healing was complete.

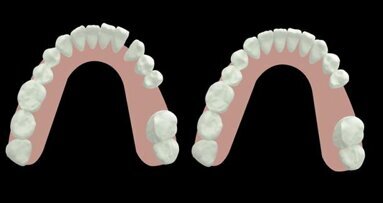

At the first appointment, the patient’s oral condition was digitised using an intra-oral scanner (TRIOS 4, 3Shape; Fig. 1). The complete dentures were designed in the Dental Designer software (3Shape). First, teeth #11 and 21 were digitally extracted. A virtual tooth set-up was then performed for both arches (Fig. 2). The morphology of the two remaining incisors determined the selection of the digital anterior teeth. The posterior teeth were selected and positioned accordingly. Subsequently, the denture base extensions were defined, and the tooth segments were adapted to the bases. The corresponding STL files were generated.

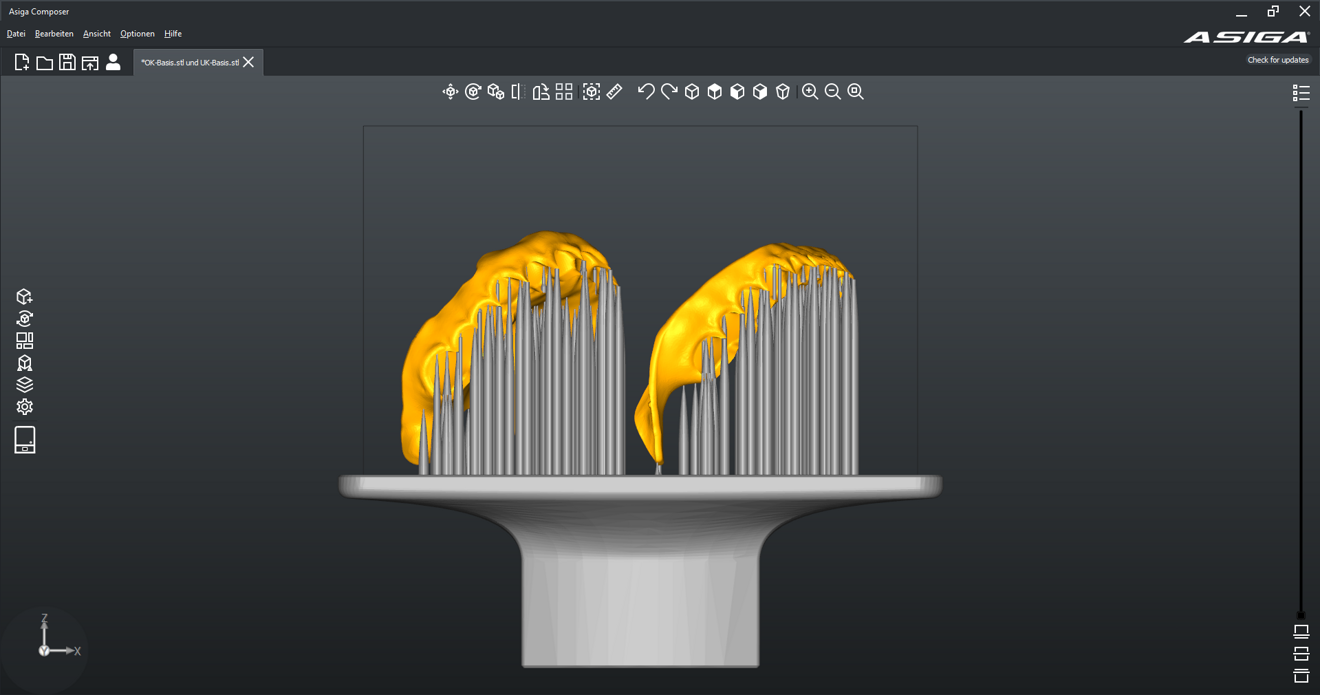

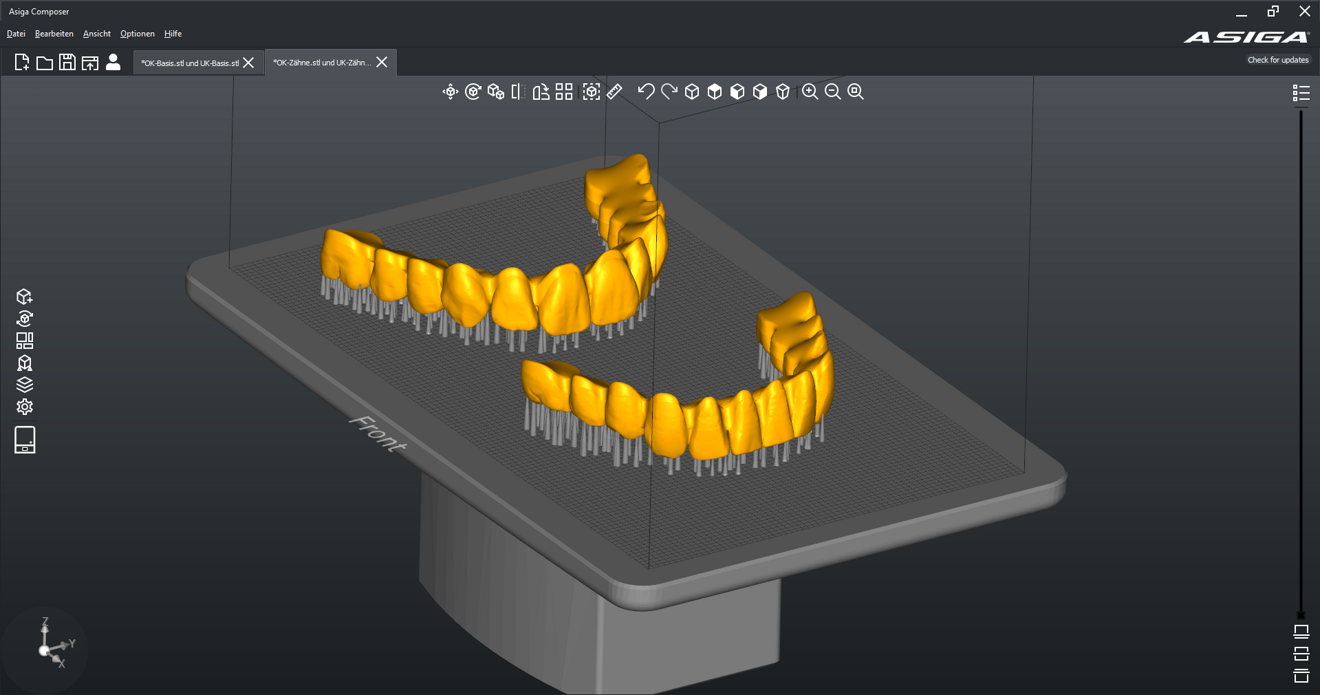

Nesting software (Composer, Asiga) was used to position the print files for the tooth segments and denture bases relative to the build plate, generate supporting structures and calculate the print job (Figs. 3 & 4). The denture bases were produced additively from V-Print dentbase (VOCO) using the MAX UV digital light processing printer (Asiga). After the printing process, the printed parts were carefully detached from the build plate and the supporting structures removed (Figs. 5 & 6). Subsequent cleaning was carried out using 98.5% isopropanol. The printed parts were immersed several times in a bath and then underwent an initial cleaning in an ultrasonic bath (SONOREX SUPER RK 102 H, BANDELIN electronic) for 3 minutes and a final cleaning in a fresh bath for 2 minutes. Secondary polymerisation was carried out in the Otoflash light polymerisation unit (2 × 2,000 flashes; NK Optik).

After post-processing, the tooth segments and denture bases were finished using carbide burs and polished on a polishing machine with pumice and goat hair brushes. Next, the fit of the tooth segments in the denture bases was verified (Fig. 7). To increase retention and improve bonding, both the tooth compartments of the denture bases and the bonding surfaces of the tooth segments were sand-blasted with 50–110 µm aluminium oxide at 100–200 kPa. Residue was removed with compressed air or a steam jet. CediTEC (VOCO) was used as the luting system. The conditioning of the luting surfaces of the denture bases and tooth segments was done with the CediTEC Primer. After application, the primer requires 30 seconds to dry (Fig. 8).

The tooth compartments of the denture bases were then filled with CediTEC Adhesive and joined together with the tooth segments (Figs. 9 & 10). Excess material was removed with a wax knife. The tooth segments were fixed to the denture bases using rubber bands before polymerisation in the pressure unit. The polymerisation time was 15 minutes at 300 kPa and a water temperature of 50 °C. After polymerisation, the interface between the denture base and tooth segments was finished, and final polishing was performed (Fig. 11).

At the next appointment, teeth #11 and 21 were extracted and the provisional dentures were inserted. After occlusal adjustments, the patient was released and returned for a follow-up two weeks later (Fig. 12).

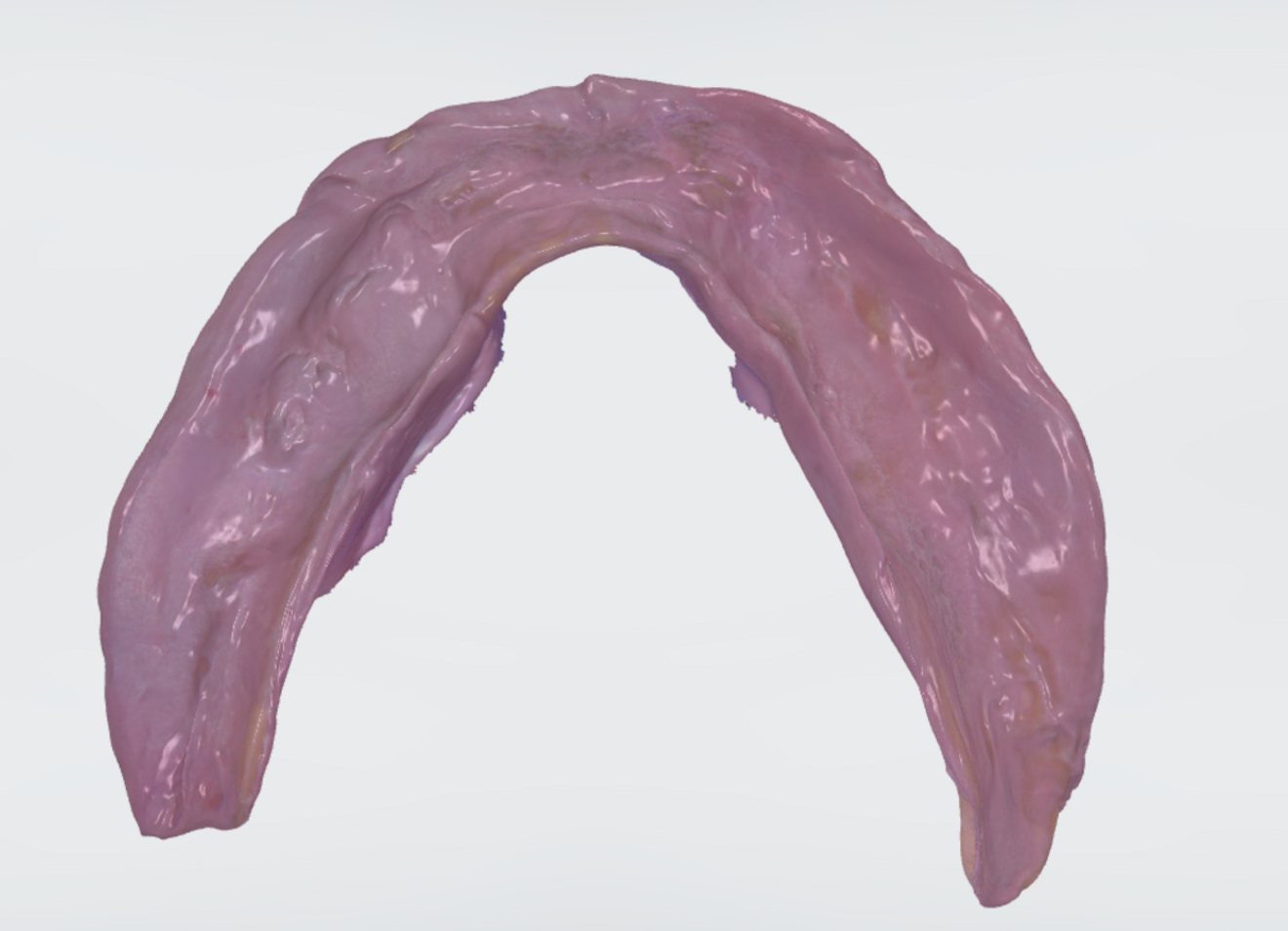

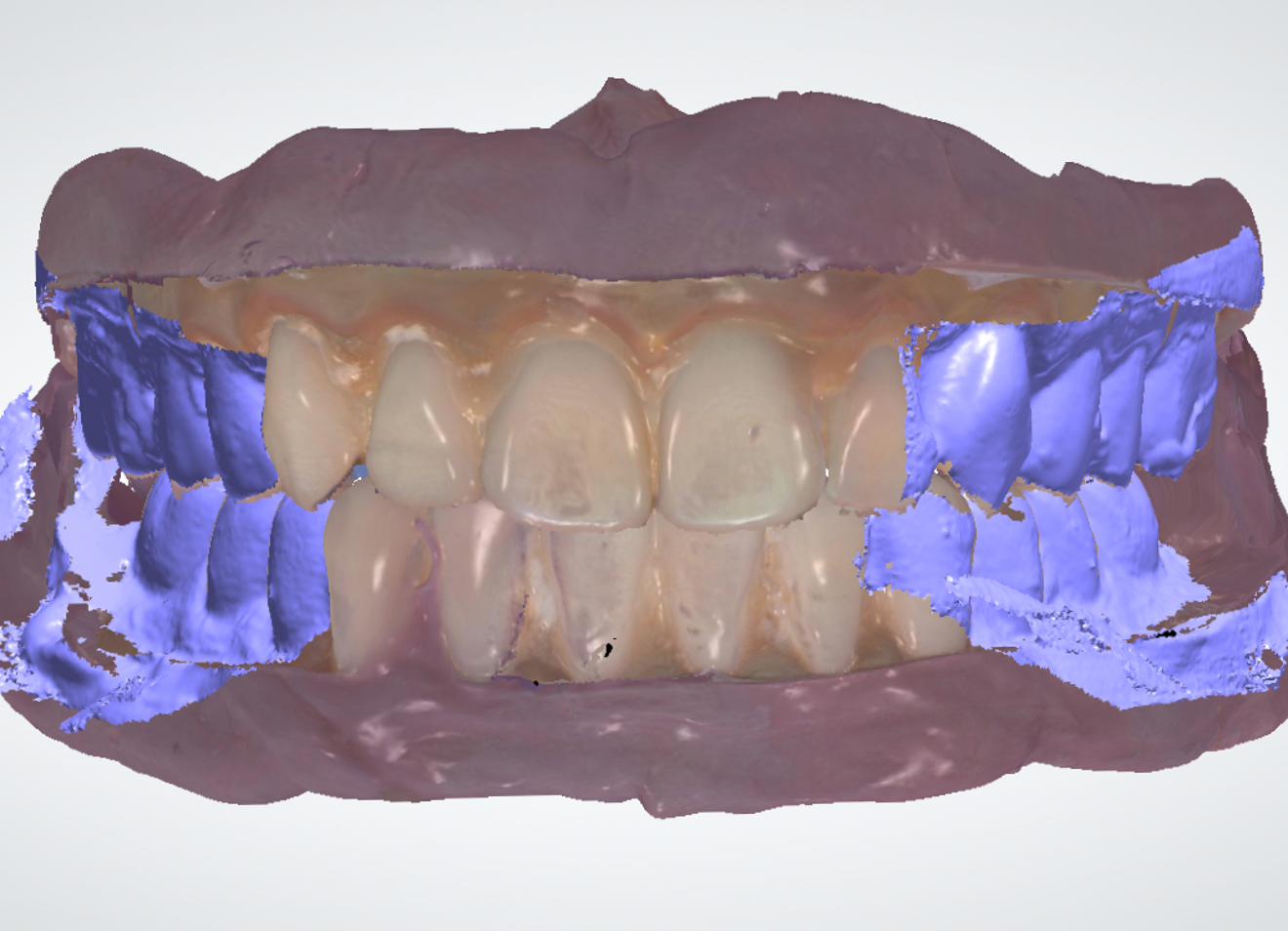

Further treatment to fabricate the definitive dentures was carried out approximately four months after extraction of the incisors. The patient was satisfied with the tooth shape, occlusal height and base extension. As intra-oral scanning cannot record the dynamic movements of the oral mucosa or capture tissue under load, the dentures were relined with Impregum Penta (Solventum) and the patient performed the corresponding movements. The dentures were then scanned in situ with the relining material in place (Figs. 13 & 14). Accurate scanning of the facial surfaces was essential for matching with the occlusal registration scan (Fig. 15).

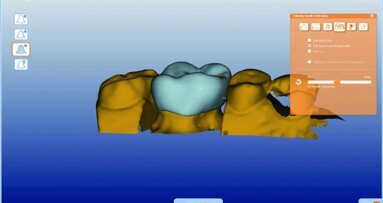

Denture design followed the same procedure as for the provisional dentures. The definitive dentures were fabricated using the five-axis milling machine inLab MC X5 (Dentsply Sirona). The STL files were first nested in the inLab CAM software (Figs. 16 & 17). The denture bases were milled from the PMMA disc CediTEC DB, and the denture teeth were milled from the composite disc CediTEC DT (Figs. 18 & 19). After milling, the connectors were trimmed and ground. Subsequently, all parts of the dentures were completely polished, and the luting surfaces of the denture base and tooth segments were conditioned (Figs. 20 & 21). Again, for luting, the CediTEC system was used as described previously. Finally, the fitting surfaces of the tooth segments and denture bases were polished (Fig. 22).

During the appointment for insertion, the fit and pressure points of the dentures were checked, the occlusion was finely adjusted and the dentures were polished to a high gloss. The patient was satisfied with the outcome (Figs. 23 & 24).

Conclusion

The digital workflow for complete dentures offers numerous advantages over conventional techniques for patients, technicians and dentists alike. These include reduction and simplification of the work steps. Intra-oral scans can be transferred directly to the laboratory without the need for shipping, eliminating work steps such as model fabrication and articulation. Digital design allows for rapid, symmetrical modification of tooth positioning. Conventional grinding of denture teeth is no longer necessary. The finished virtual design can be reviewed with the patient beforehand, reducing the number of subsequent adjustments. Moreover, saved designs allow for quick reproduction in case of prosthesis loss or the need for travel prostheses.3 The digital approach therefore contributes to more time- and cost-efficient treatment.4

CAD/CAM fabrication also enables the processing of new materials. Milled blanks have lower residual monomer content, improved homogeneity, and higher flexural and fracture strength.5–8 As a result, prostheses can be designed more delicately and are less susceptible to discoloration.9 While conventionally manufactured prostheses made from heat-polymerised PMMA exhibit polymerisation shrinkage, this is eliminated in subtractive manufacturing, resulting in a higher accuracy of fit.10, 11

While subtractive manufacturing methods are well established, additive manufacturing is becoming increasingly popular. 3D printing offers a fast, material-saving alternative for producing try-ins, provisional prostheses and definitive dentures. It allows for multiple items to be produced simultaneously and for reconstruction of areas with large undercuts without any problems. The investment costs for desktop 3D printers are also significantly lower.12 Although additively manufactured prostheses are equal to conventionally manufactured prostheses in many respects, they still have material-specific disadvantages compared with subtractively manufactured prostheses. These include lower flexural strength and fracture resistance and an increased tendency to discoloration.13 Furthermore, the user-sensitive post-processing and the manufacturing process can result in variation in the material-specific properties and ultimately lead to differences in quality.13

The combination of additive and subtractive processes may revolutionise future denture fabrication and enable more efficient, individualised patient care. Stratasys’s PolyJet process, which enables multi-material printing, is a promising advancement beyond current stereolithography and digital light processing technologies.12 In the future, dentures could be printed in a single step from layers of materials with various mechanical properties, allowing for highly individualised designs with optimised aesthetics and functionality.

Austria / Österreich

Austria / Österreich

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bulgaria / България

Bulgaria / България

Croatia / Hrvatska

Croatia / Hrvatska

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

France / France

France / France

Germany / Deutschland

Germany / Deutschland

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Hungary / Hungary

Hungary / Hungary

Italy / Italia

Italy / Italia

Netherlands / Nederland

Netherlands / Nederland

Nordic / Nordic

Nordic / Nordic

Poland / Polska

Poland / Polska

Portugal / Portugal

Portugal / Portugal

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Slovenia / Slovenija

Slovenia / Slovenija

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Spain / España

Spain / España

Switzerland / Schweiz

Switzerland / Schweiz

Turkey / Türkiye

Turkey / Türkiye

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

Brazil / Brasil

Brazil / Brasil

Canada / Canada

Canada / Canada

Latin America / Latinoamérica

Latin America / Latinoamérica

USA / USA

USA / USA

China / 中国

China / 中国

India / भारत गणराज्य

India / भारत गणराज्य

Pakistan / Pākistān

Pakistan / Pākistān

Vietnam / Việt Nam

Vietnam / Việt Nam

ASEAN / ASEAN

ASEAN / ASEAN

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Middle East / Middle East

Middle East / Middle East

To post a reply please login or register