The European Aligner Society recently held its sixth congress, on the island of Rhodes in Greece, and offered a programme that delivered insights and expertise from the leading minds in aligner orthodontics. One of these speakers was orthodontist Dr Morten G. Laursen, who is a senior clinical instructor in dentistry at Aarhus University in Denmark and runs a private orthodontic practice in Aarhus. During the congress, he presented a paper titled “The role of aligners in the treatment of gingival recession” that addressed the relevance of the dentoalveolar complex, his research focus, and he talks to Dental Tribune International in this interview about the importance of assessing the hard and soft tissue and planning treatment accordingly.

Dr Laursen, how is the dentoalveolar complex relevant to treating gingival recession, particularly with aligners?

During research conducted some years ago, we collected dentoalveolar samples from autopsy cases and scanned them using micro-CT—a technique that provides highly detailed visualisation of teeth and the surrounding bone. This allowed us to precisely measure buccal and lingual bone thickness. What we found was striking: in many cases, the bone was extremely thin or even absent, and we frequently observed dehiscences and fenestrations, particularly in the anterior mandible—and yet, this is the very region where we routinely move teeth during orthodontic treatment. The anterior mandibular region is particularly prone to gingival recession after orthodontic treatment. We often see this with fixed retainers—especially when they inadvertently become active, leading to root movement. It doesn’t take much to breach the already thin cortical plate, resulting in dehiscence. Once the bone is compromised, the overlying soft tissue loses support, and recession can occur. At that point, the tooth has essentially lost its protective coverage; both attachment and support are compromised.

This research has made me acutely aware of anatomical limitations, particularly how much—and in whom—we can safely move teeth. The risk varies significantly from patient to patient. We often talk about moving teeth through bone versus with bone. While tooth movement with bone is sometimes possible, it’s not predictably achievable across all cases. That’s where phenotyping becomes critical.

By assessing hard- and soft-tissue biotypes, we can better predict outcomes. Patients with thick bone and thick soft tissue can typically tolerate more aggressive movements with minimal risk. Conversely, in those with thin biotypes, even minor movements can lead to complications. So, understanding individual anatomy and respecting biological boundaries are key—especially when planning treatment with aligners, which may offer advantages in terms of controlled and gradual forces, but do not eliminate the underlying anatomical risks.

How important is it for orthodontists to assess the patient’s bone and soft-tissue phenotype before planning tooth movement—and do you think that this is standard practice in the profession today?

I believe that diagnostic attention is absolutely essential. While CBCT imaging can be very useful in some cases, it’s not always necessary. There’s still a lot we can assess through clinical examination. Simple palpation and inspection of the soft tissue can give us valuable insights into the underlying bone anatomy.

Sometimes, the alveolar bone is actually narrower than the root itself, which makes certain tooth movements particularly risky. This is why it’s so important to remain aware of these anatomical limitations in our daily practice—because the consequences of overlooking them may only become apparent years later. You might initially have a bony dehiscence that’s still covered by soft tissue, but over time, that tissue may recede and the underlying issue become exposed.

It’s critical to assess what kind of biological environment you’re working in. Does the patient have a thick biotype, where the risk of complications is minimal? Or is it a thin phenotype, where both the bone and soft tissue are fragile and susceptible to damage? In either case, proper diagnosis is key.

From there, you have to consider your treatment plan carefully—especially the force vector of tooth movement. If you’re planning to move teeth labially in the anterior region or significantly lingually in the posterior, you may be moving them out of the alveolar envelope. In such cases, it may be necessary to rethink the biomechanics entirely to avoid compromising long-term periodontal stability.

In your lecture, you pointed to the value of the clinician’s eyes and hands in making assessments. So, in this digital age, how do you balance clinical intuition with digital tools in monitoring treatment progress and root positioning?

Before starting treatment, I always palpate the roots. If the roots are well positioned within the alveolar bone, you won’t be able to feel them—and that’s reassuring. But if you can detect root prominence through the bone, especially when you’re planning anterior movements, it’s important to monitor these teeth closely throughout treatment. A lot can be assessed visually and manually.

Of course, clinical examination doesn’t reveal everything—and that leads to the ongoing debate around the appropriate use of CBCT. For instance, if a malocclusion has been caused by a bonded retainer that has moved the teeth significantly out of the alveolar envelope, and there’s doubt about the prognosis of those teeth, then I would definitely consider taking a CBCT scan. In such cases—where tooth loss is a possible outcome or where we’re evaluating whether a tooth can be retained—I use CBCT regularly.

However, it’s important to understand its limitations. If we’re simply trying to determine whether there’s a minimal amount of bone covering a root, CBCT lacks the resolution to show that level of detail accurately. In Denmark, we cannot take CBCT scans on all patients by default; there are specific clinical indications required for its use.

So, while digital tools are invaluable, they don’t replace the clinician’s tactile and visual assessment. Our eyes and hands remain some of the best diagnostic tools we have—especially when used with intent and experience.

You highlighted that mandibular incisors are especially susceptible to recession owing to thin surrounding bone. How can clinicians assess and manage this risk during treatment planning with aligners?

The first step is simply to look and then to palpate. I think that’s sometimes what gets overlooked. When we intentionally look for something, we begin to recognise it more often. Gingival recession, in particular, is a real and common problem, but it can go unnoticed if we’re not consciously assessing for it.

I have a story from a periodontist I work closely with. She was giving a course to a group of orthodontists on surgical techniques for covering recession defects. A few months later, she ran into one of the participants, and he said, “It’s so strange: since your course, we’ve been seeing so many more recessions!” Of course, the difference wasn’t that the cases had increased but that the orthodontists had started looking more carefully—and now they were seeing them.

This highlights an important point: awareness changes perception. By training ourselves to routinely assess the gingival margin, root prominence and tissue biotype—especially in high-risk areas like the mandibular incisors—we’re more likely to identify risks early and adapt our treatment plans accordingly, particularly when working with aligners.

In terms of biomechanics, you mentioned in your lecture that aligners can apply a force couple to guide root movement. Could you elaborate on how this helps reduce unintended side effects compared with fixed appliances?

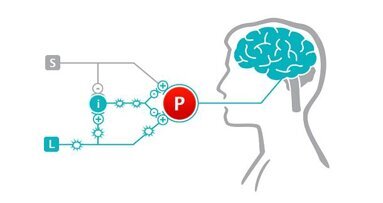

The concept of a force couple—two equal and opposite forces applied to produce controlled rotation or root movement—can be applied with both fixed appliances and aligners. However, the key difference lies in how precisely we can control these forces and manage side effects, especially in anatomically delicate situations.

With fixed appliances, particularly in cases involving very thin alveolar bone, thin gingival tissue, and roots displaced partially outside the alveolar bony housing—such as patients with active retainers/wire syndrome already presenting with or at risk of recession—biomechanical control becomes more challenging. When using a continuous archwire across multiple brackets, any activation generates a cascade of reactions throughout the entire arch. This makes it difficult to isolate and control the movement of individual roots, unless the force system is biomechanically consistent—which is rarely the case in clinical reality.

In these situations, round-tripping—moving a tooth in the wrong direction before bringing it back—can be detrimental. Thin bone doesn’t allow for such unnecessary excursions. That’s where segmental mechanics comes into play. By avoiding a continuous wire and instead using isolated brackets and sections of wire, we can treat a few teeth at a time with greater control. This method is effective but time-consuming. It requires careful planning, precise wire bending and close monitoring throughout treatment.

Regarding aligners, however, my experience is that we can often approach these complex movements more efficiently. Because the aligner encompasses the entire tooth—including both the buccal and lingual cervical margins—it provides, to some extent, a kind of built-in anchorage and containment. However, it should be recognised that the material is flexible, therefore, compensatory torque movement of neighbouring teeth should be considered for additional anchorage.This allows us to better manage root positioning and reduce unwanted reciprocal movements. For example, when we move a tooth in one direction, we can more effectively prevent the adjacent teeth from reacting undesirably, which is much harder to achieve with fixed appliances. In essence, aligners can offer a unique advantage in controlling force couples for root torque in a more predictable way, particularly in cases where we must be mindful of biological boundaries.

You spoke about the importance of diagnosis and planning when dealing with a thin gingival biotype. What diagnostic tools or clinical signs do you prioritise when deciding whether aligner therapy is appropriate or not?

When treating patients with roots displaced partially outside the alveolar bone in a thin gingival phenotype—particularly in cases involving or at risk of recession—I generally prefer aligner therapy. In fact, I almost always choose aligners in these situations.

These cases are often retreatments, and the patients are typically adults who appreciate the comfort and aesthetics of aligners. Beyond patient preference though, aligners offer excellent biomechanical control. One of the key advantages is the ability to minimise unwanted side effects, which is particularly important in patients with thin hard and soft tissue.

From a clinical perspective, aligners allow for precise, incremental movements and better control of force vectors—especially important when moving teeth within biologically constrained environments. Based on experience alone, aligner therapy has proved to be an effective and quite predictable tool for managing these cases, provided individual and careful planning of tooth movements and aligner biomechanics. That’s why I consistently recommend aligners when treating displaced teeth with recession in a delicate gingival phenotype.

Dr Domingo Martín asserted in his presentation that 70% of initial visits to the orthodontist’s practice are for retreatments due to poor diagnosis. Have you found this to be the case?

We do see a fair number of retreatment cases in practice, but they don’t make up the majority of our patients.

In my experience, it’s important to view fixed appliances and aligners as complementary tools. I use both regularly, depending on the patient’s needs. Some cases are best managed entirely with aligners and others with fixed appliances, and often I combine the two approaches—starting treatment with fixed appliances and finishing with aligners, or vice versa. This approach also applies to orthognathic cases. Ultimately, the focus should be on selecting the best treatment modality for each patient to achieve optimal results.

At a congress dedicated to aligners, it’s especially important to recognise that fixed appliances still have a crucial role in orthodontics. It seems from what you’ve just said that you would agree.

Absolutely. I think it’s essential to understand when one tool is better suited than another. Many patients come to the consultation requesting aligners, which is understandable. However, there are cases where aligners simply aren’t the optimal choice to achieve the desired outcome.

I often use an analogy to help patients understand this: if you had to drive across a desert, would you choose a Ferrari or a Jeep? Most would pick the Jeep, because it’s the right tool for that terrain. Similarly, in orthodontics, it’s about selecting the right option for the treatment challenges we face. My goal is always to recommend the best tool—whether aligners, fixed appliances or a combination—to deliver the most effective and predictable results.

Topics:

Tags:

Exocad, an Align Technology company and one of the leading providers of dental CAD/CAM software, is set to showcase the next level of dental CAD design at ...

Henry Schein aims to provide every product that a practitioner may need, with a strong focus on value-added services and solutions. As CEO Stanley Bergman ...

The recent ADA FDI World Dental Congress 2019, held at the Moscone Center in San Francisco from Sept. 4–8, saw the conclusion of Dr. Kathryn Kell’s ...

Dentsply Sirona, the world’s largest manufacturer of professional dental products and technologies, has adeptly positioned itself as the leading force in ...

TAI’AN, China: An experienced surgeon, Dr Guangyong Wan has been a Planmeca end user for more than 30 years. Based at the Tai’an City Central ...

Dr. Sammy Noumbissi, founder and President of the International Academy of Ceramic Implantology (IAOCI), is currently organizing the academy’s 7th annual ...

The popularity of clear aligners has surged in recent years, making them a preferred orthodontic solution for many patients.1–3 However, the success of ...

LEIPZIG, Germany: A couple of weeks ago, the US company 4Ocean, which specialises in removing plastic waste from the ocean, shared a post on Facebook that ...

Every dentist is looking to grow his or her practice, and we are all looking to bring in as many new patients as we can. Numerous excellent articles have ...

Ectopic canines are a complex condition to treat with aligners only, since it is not easy to create a reliable and stable anchorage unit for forced ...

Live webinar

Tue. 24 February 2026

1:00 pm EST (New York)

Prof. Dr. Markus B. Hürzeler

Live webinar

Tue. 24 February 2026

3:00 pm EST (New York)

Prof. Dr. Marcel A. Wainwright DDS, PhD

Live webinar

Wed. 25 February 2026

11:00 am EST (New York)

Prof. Dr. Daniel Edelhoff

Live webinar

Wed. 25 February 2026

1:00 pm EST (New York)

Live webinar

Wed. 25 February 2026

8:00 pm EST (New York)

Live webinar

Tue. 3 March 2026

11:00 am EST (New York)

Dr. Omar Lugo Cirujano Maxilofacial

Live webinar

Tue. 3 March 2026

8:00 pm EST (New York)

Dr. Vasiliki Maseli DDS, MS, EdM

Austria / Österreich

Austria / Österreich

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bulgaria / България

Bulgaria / България

Croatia / Hrvatska

Croatia / Hrvatska

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

France / France

France / France

Germany / Deutschland

Germany / Deutschland

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Hungary / Hungary

Hungary / Hungary

Italy / Italia

Italy / Italia

Netherlands / Nederland

Netherlands / Nederland

Nordic / Nordic

Nordic / Nordic

Poland / Polska

Poland / Polska

Portugal / Portugal

Portugal / Portugal

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Slovenia / Slovenija

Slovenia / Slovenija

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Spain / España

Spain / España

Switzerland / Schweiz

Switzerland / Schweiz

Turkey / Türkiye

Turkey / Türkiye

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

Brazil / Brasil

Brazil / Brasil

Canada / Canada

Canada / Canada

Latin America / Latinoamérica

Latin America / Latinoamérica

USA / USA

USA / USA

China / 中国

China / 中国

India / भारत गणराज्य

India / भारत गणराज्य

Pakistan / Pākistān

Pakistan / Pākistān

Vietnam / Việt Nam

Vietnam / Việt Nam

ASEAN / ASEAN

ASEAN / ASEAN

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Middle East / Middle East

Middle East / Middle East

To post a reply please login or register