Looking beyond the field of dentistry and seeking ways to implement scientific advancements in root canal treatment is a sensitive undertaking—yet one that can be highly rewarding when new insights and ideas emerge. Heat treatment in metallurgy dates back to the Iron Age, and still today, we are discovering innovative ways to apply it to nickel–titanium (NiTi) in order to produce safer rotary files.

It all began with Twisted Files from Sybron Endo (today part of Kerr Dental)—the first time that heat treatment was applied to NiTi rotary files—starting a new chapter in root canal therapy. Years later, a different approach to heat treatment was introduced, allowing engineers to combine two distinct alloy structures within a single file. This innovation brought greater safety and built-in flexibility to rotary instrumentation. ZenFlex (Kerr Dental) is one such example, taking file technology to a new level with a fresh perspective.

But how should these files be used? Is a single-file approach the right choice? Or should we employ a sequence? The core question remains: should all root canals be approached the same way? Can we treat every tooth—even within the same patient—the same way? What about the variation between patients and canal anatomies? The answer lies in the anatomy itself. We must adapt our instrumentation to the canal anatomy—not the other way around. Anatomy cannot be standardised, and it is up to the clinician to select the appropriate sequence to shape the canal. Of course, shaping is just one step of the treatment. The key to a successful root canal therapy lies in irrigation.

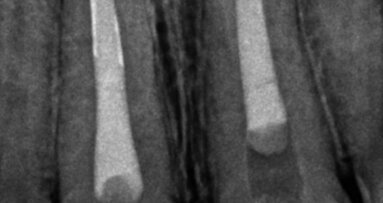

Another advantage of the new procedure used in the creation of ZenFlex files lies in the development of an exceptionally sharp cutting edge (Fig. 1). As it is responsible for the actual cutting of dentine and therefore the shaping of the canal, the cutting edge is the essential working component of any file. This innovation brings multiple benefits: improved rotational speed, better preservation of the original anatomy, reduced working time within the canal, enhanced safety—and many more.

Building on the benefits of ZenFlex files, Kerr developed ZenFlex CM files, which are produced through an advanced heat treatment process that lowers the percentage of austenite and increases the martensite—without compromising any of the file’s core features. This new generation of ZenFlex offers greater flexibility while maintaining the same cutting efficiency and level of safety. Clinically, we have observed several advantages of both generations of ZenFlex files:

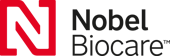

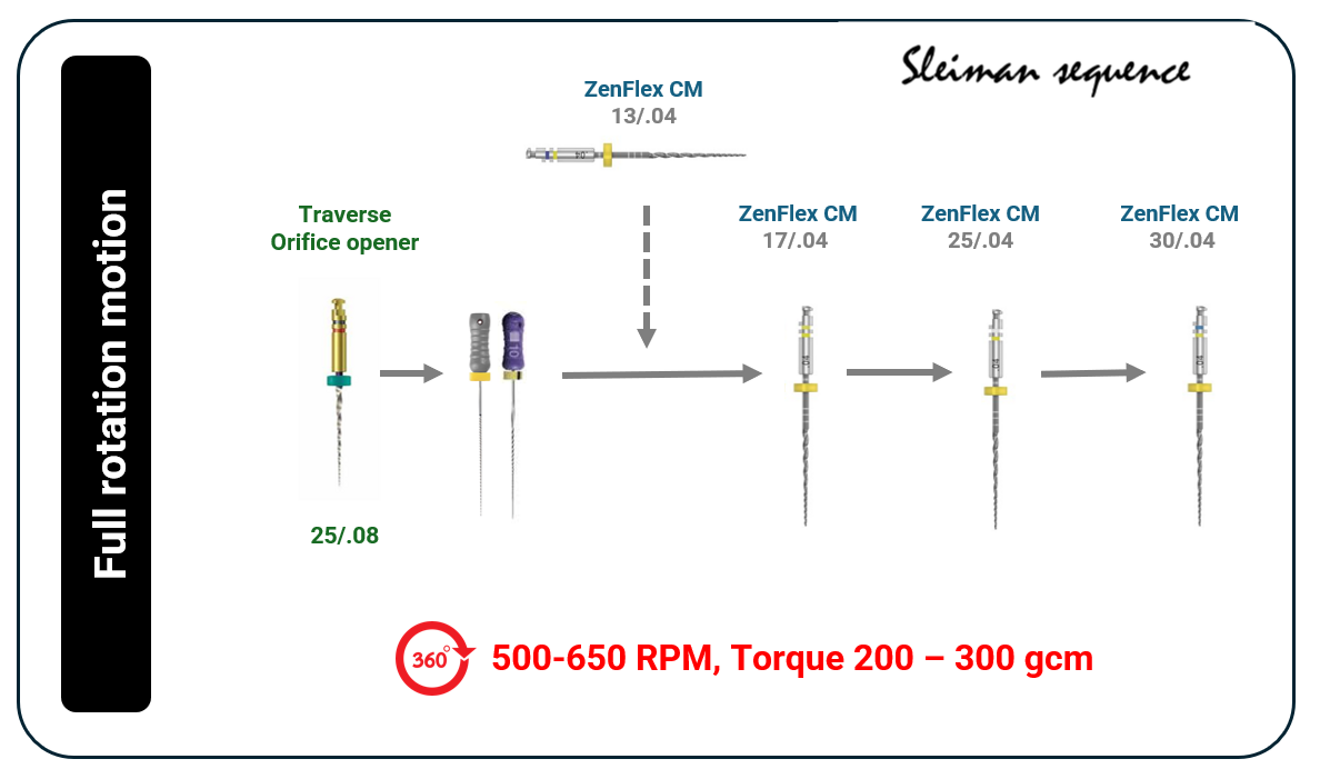

- These files can be used in full rotation as well as in Adaptive Motion—a combination of continuous rotation and reciprocation (Figs. 2 & 3). The angle of rotation depends on the level of stress within the canal: when stress is low, the adaptive angles remain small, and vice versa.

- Fewer files are needed during the procedure.

- The 13/0.04 ZenFlex CM file is an excellent tool for extremely narrow canals, creating an initial shape that guides the subsequent files.

The new file sequence can address the majority of clinical situations. Whether using continuous rotation or Adaptive Motion, the system offers the flexibility and performance to address different anatomical challenges.

Adaptive Motion offers many advantages. The variable clockwise and counterclockwise movements, adjusted according to the stress within the canal, reduce the overall stress on the file. This leads to improved debris removal compared with standard reciprocation while maintaining excellent cutting efficiency—especially in curved and complex canals. However, this approach requires equipment with software capable of supporting Adaptive Motion.

Austria / Österreich

Austria / Österreich

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bulgaria / България

Bulgaria / България

Croatia / Hrvatska

Croatia / Hrvatska

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

France / France

France / France

Germany / Deutschland

Germany / Deutschland

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Hungary / Hungary

Hungary / Hungary

Italy / Italia

Italy / Italia

Netherlands / Nederland

Netherlands / Nederland

Nordic / Nordic

Nordic / Nordic

Poland / Polska

Poland / Polska

Portugal / Portugal

Portugal / Portugal

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Slovenia / Slovenija

Slovenia / Slovenija

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Spain / España

Spain / España

Switzerland / Schweiz

Switzerland / Schweiz

Turkey / Türkiye

Turkey / Türkiye

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

Brazil / Brasil

Brazil / Brasil

Canada / Canada

Canada / Canada

Latin America / Latinoamérica

Latin America / Latinoamérica

USA / USA

USA / USA

China / 中国

China / 中国

India / भारत गणराज्य

India / भारत गणराज्य

Pakistan / Pākistān

Pakistan / Pākistān

Vietnam / Việt Nam

Vietnam / Việt Nam

ASEAN / ASEAN

ASEAN / ASEAN

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Middle East / Middle East

Middle East / Middle East

To post a reply please login or register