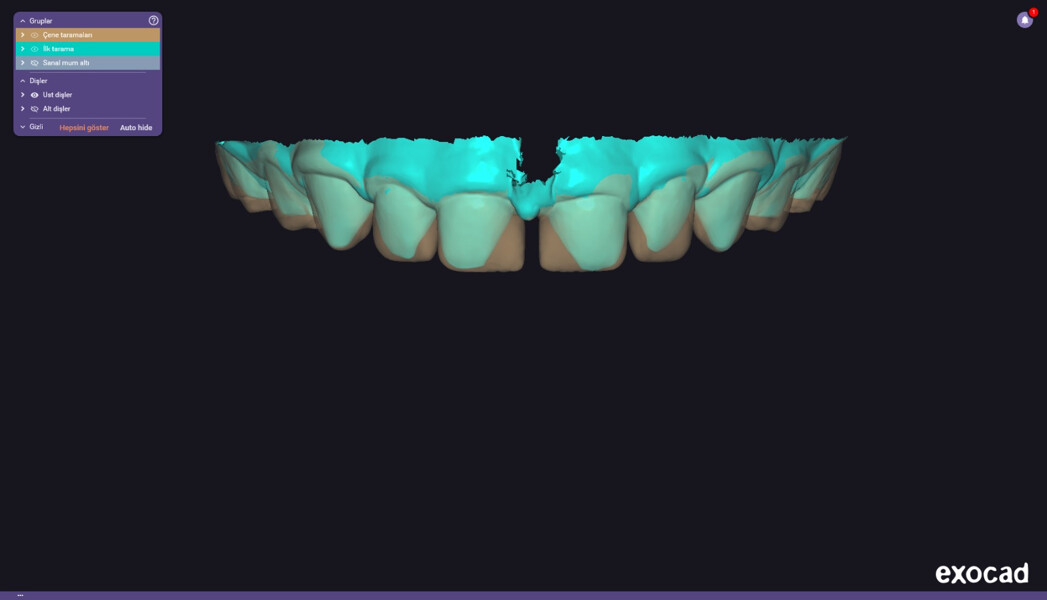

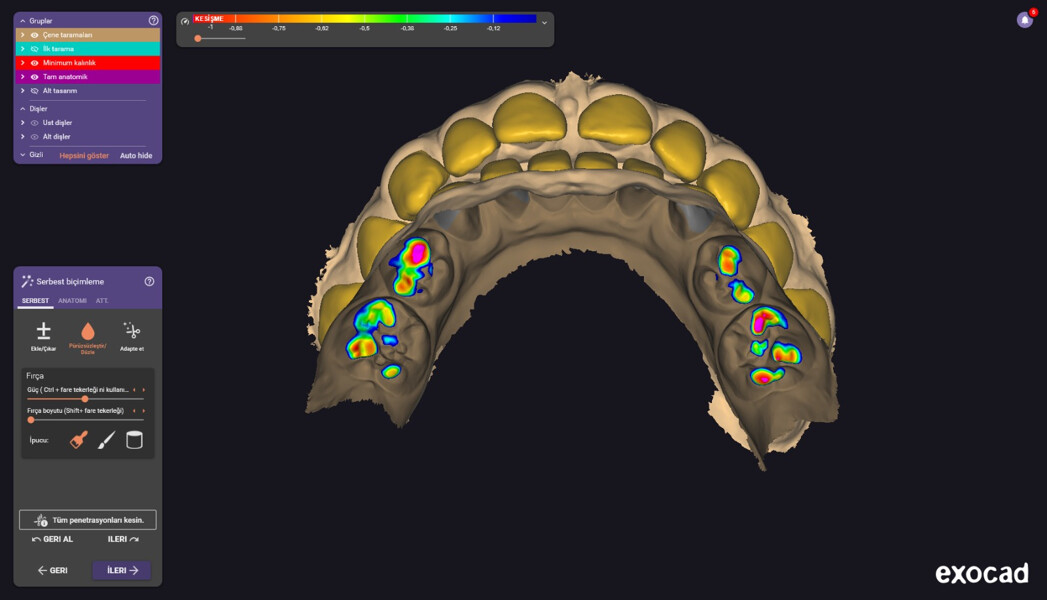

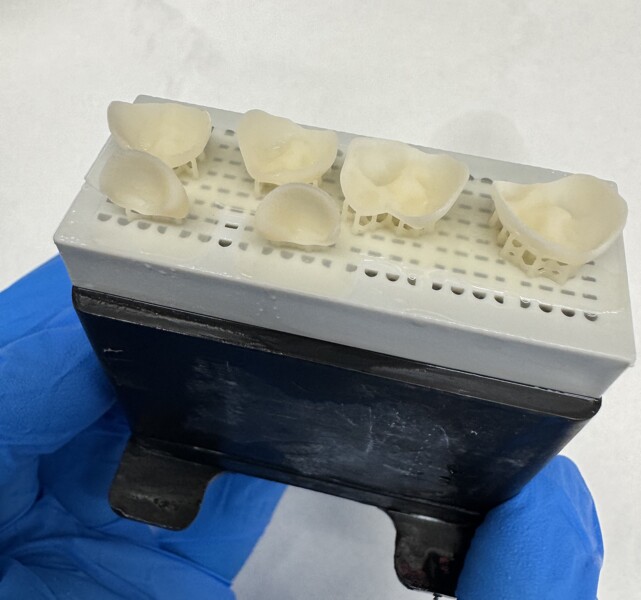

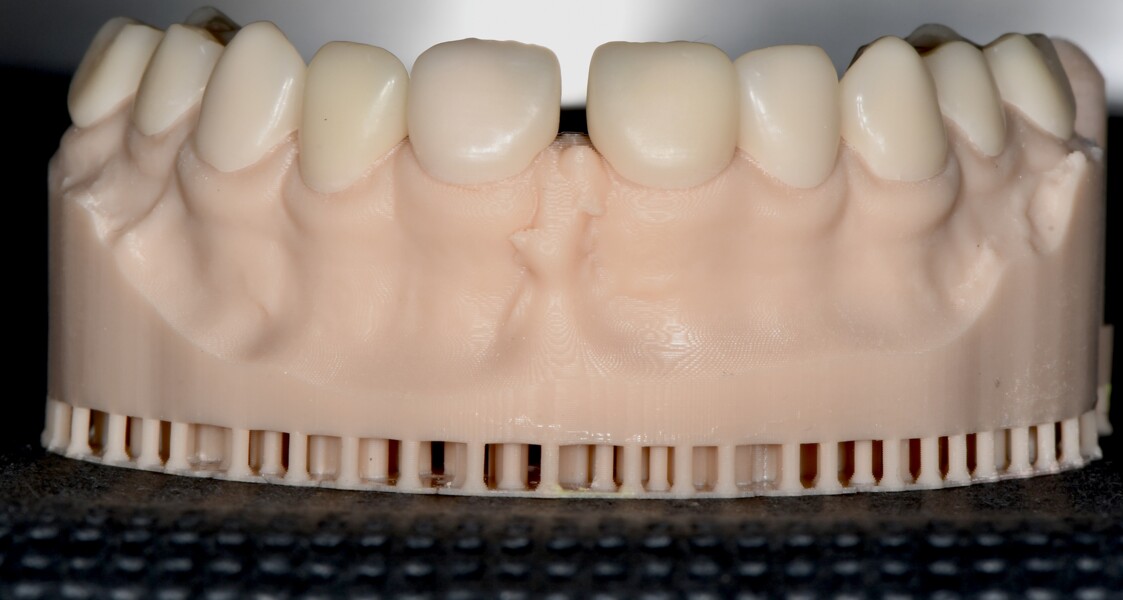

Occlusal elevation was essential to address the deep overbite with mucosal impingement, and the restorations were delivered using a simplified cementation protocol optimised for paediatric patients. A dual-polymerising resin cement and corresponding adhesive system were selected for their ease of use, effectiveness and reduced procedural steps, critical factors in managing treatment within the behavioural limits of very young children. The result met clinical and parental expectations, although the cementation and excess cement removal presented a challenge owing to limited access and patient cooperation. Within these constraints, 3D-printed composite restorations demonstrated favourable clinical performance and represent a viable, minimally invasive treatment modality for managing functional and aesthetic needs in the primary dentition, particularly in cases involving dental anomalies such as ED.

Discussion

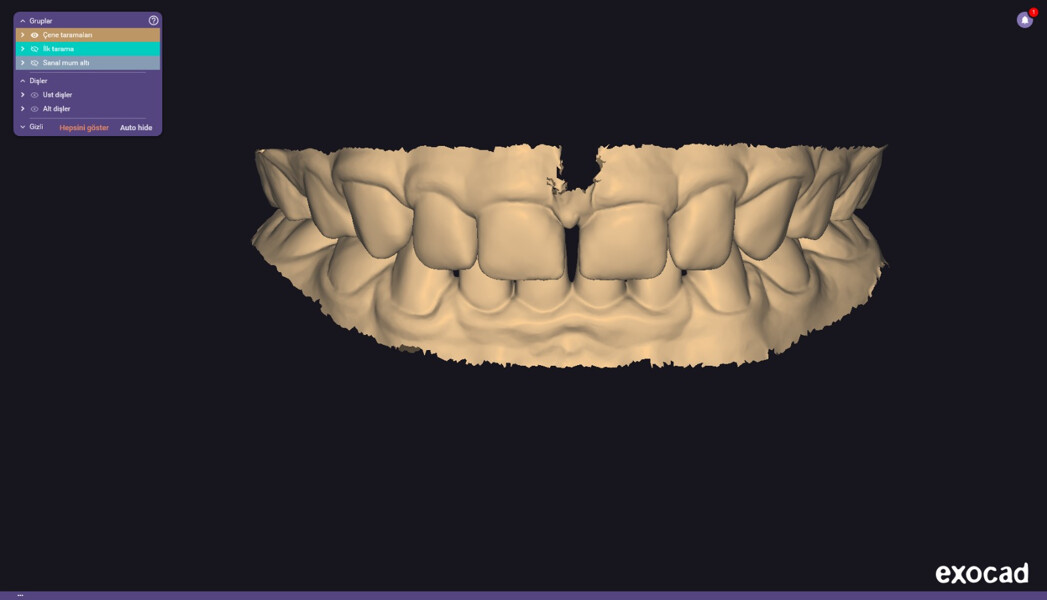

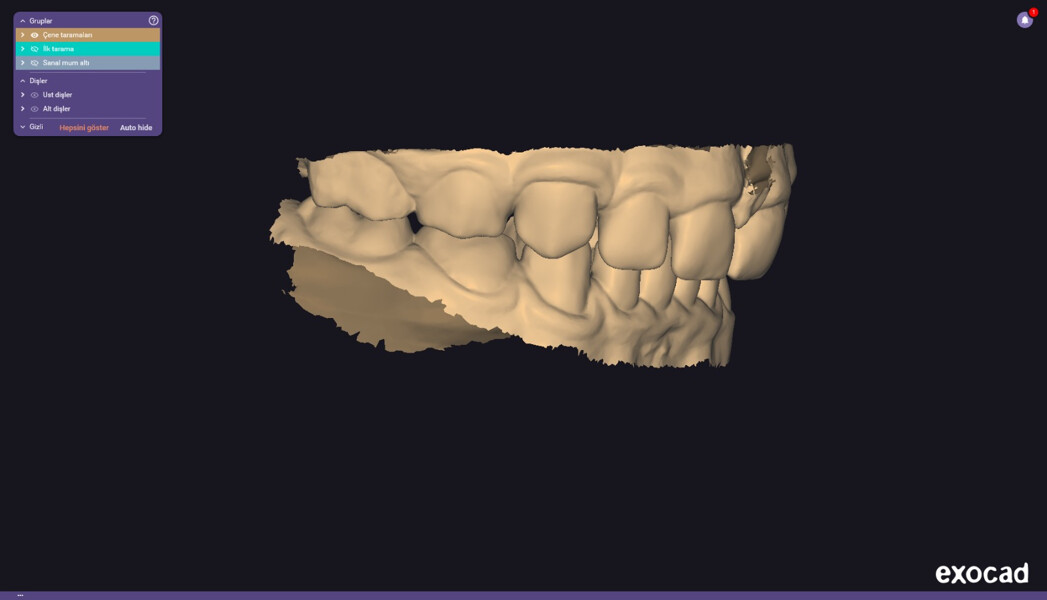

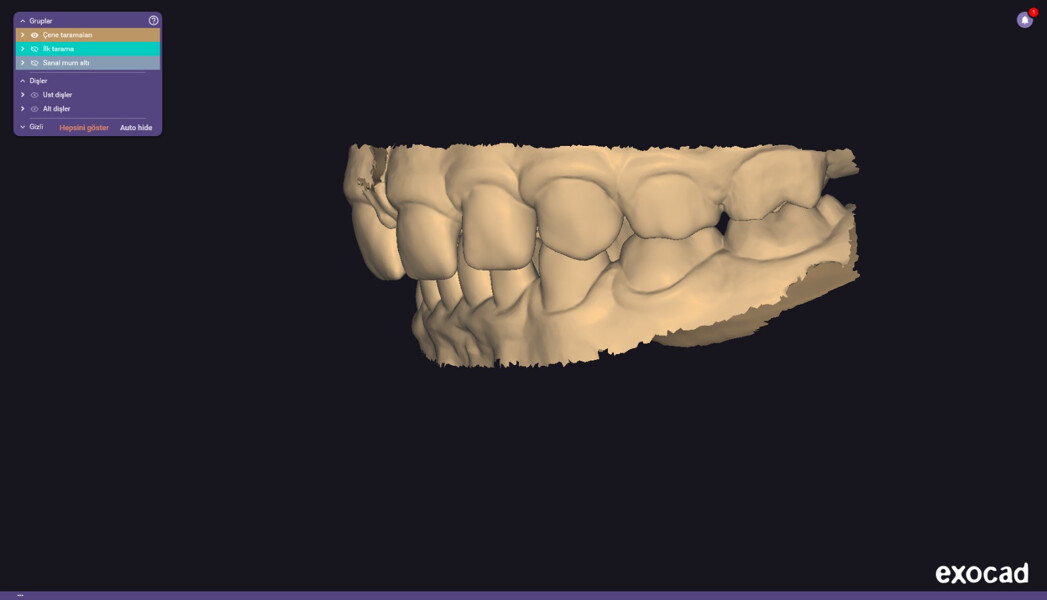

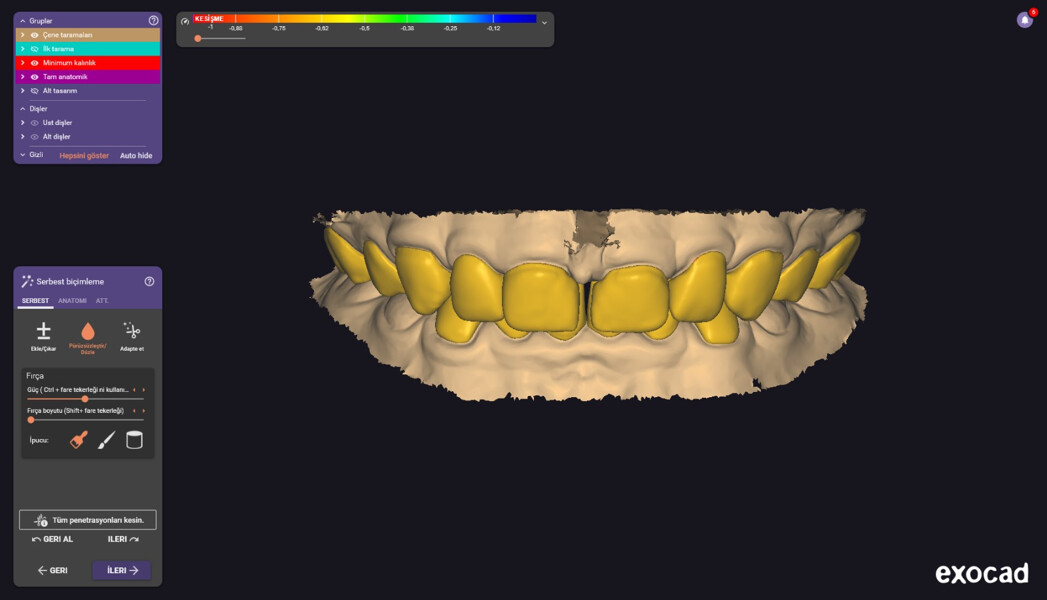

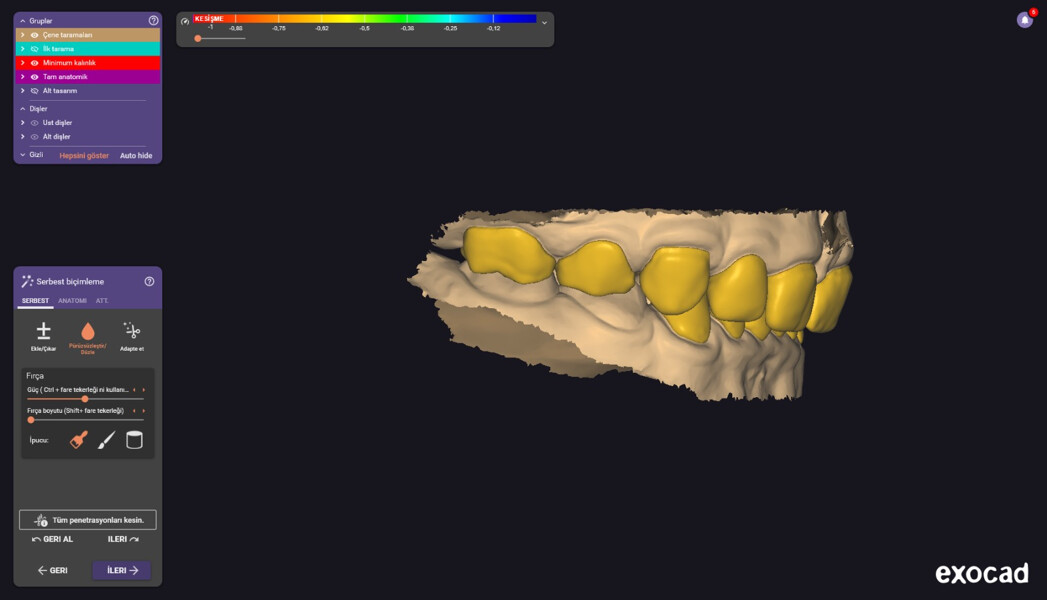

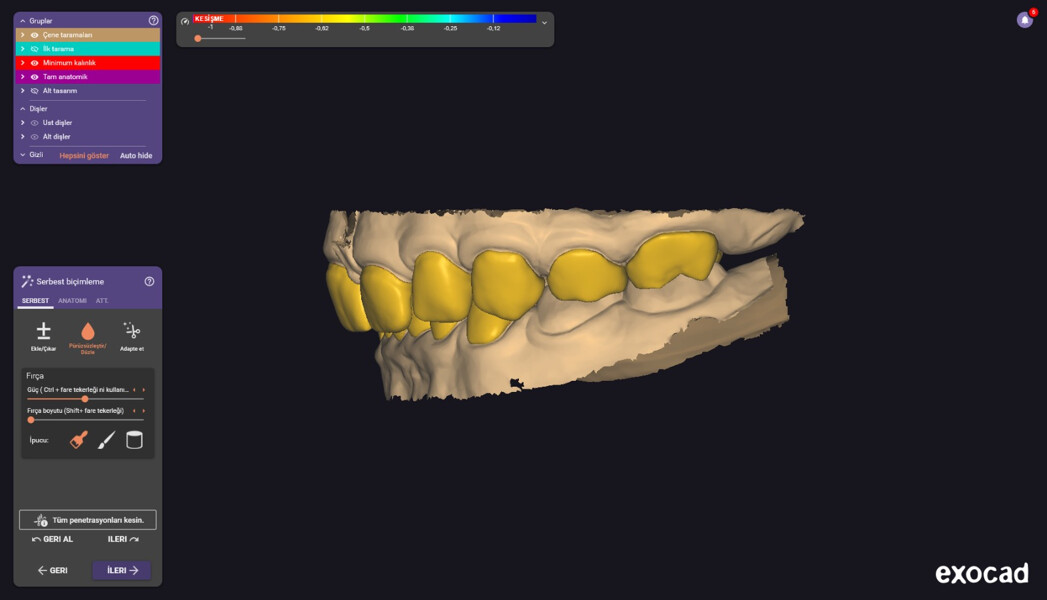

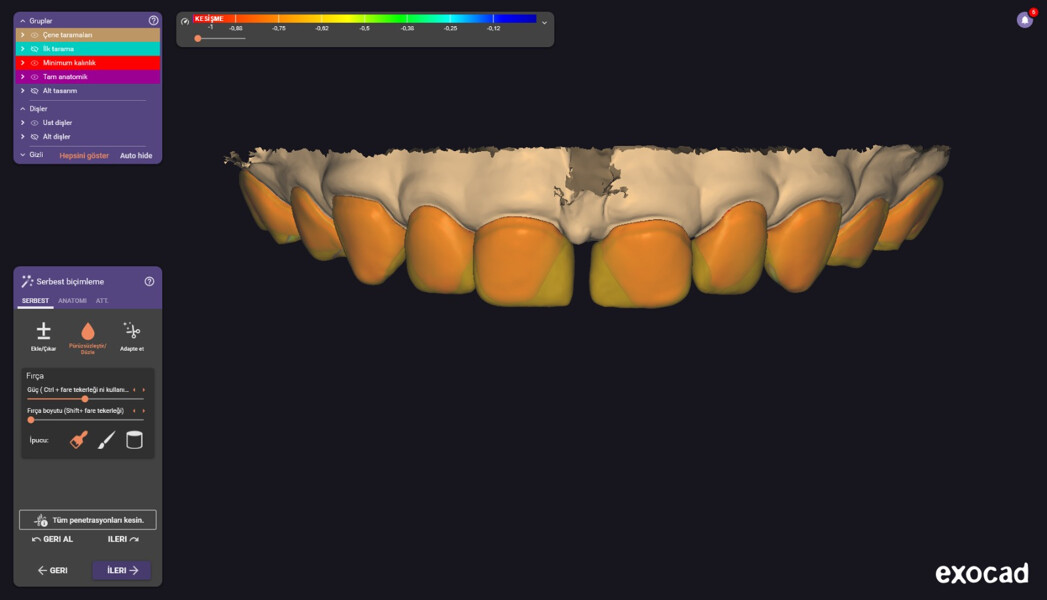

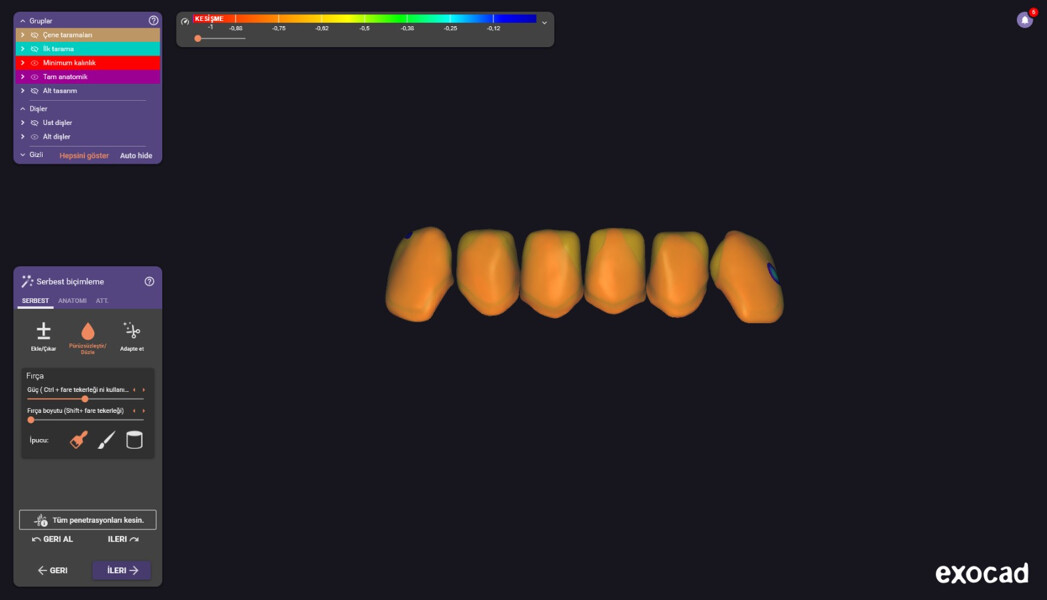

ED exhibits unique challenges in paediatric dental care owing to its early-onset impact on tooth development, facial aesthetics, oral function and psychosocial well-being. Previous studies have demonstrated that CAD/CAM-fabricated complete dentures, as well as overdentures, can be used as a solution for ED patients with a high aesthetic success rate.13 In the present case, a minimally invasive, aesthetically driven and functionally restorative approach was employed using chairside 3D-printed hybrid resin composite restorations in a 3.5-year-old child diagnosed with suspected ED. The treatment aimed to address pronounced dental anomalies, including conical anterior teeth, reduced vertical dimension of occlusion and deep overbite with mucosal impingement, all following a minimally invasive protocol owing to the patient’s age and simultaneously avoiding the use of local anaesthesia.

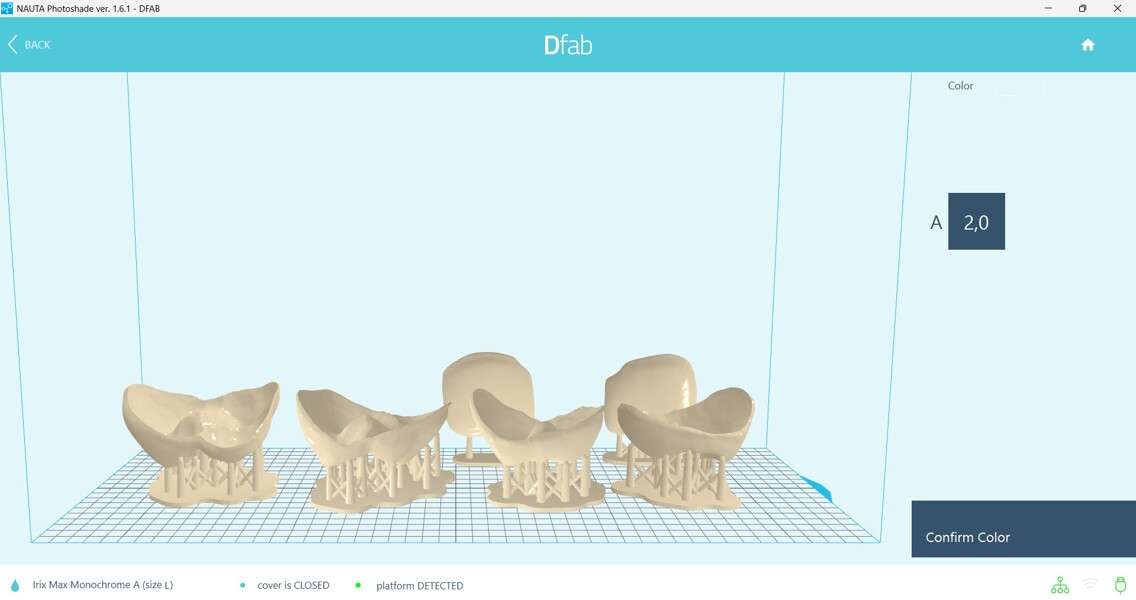

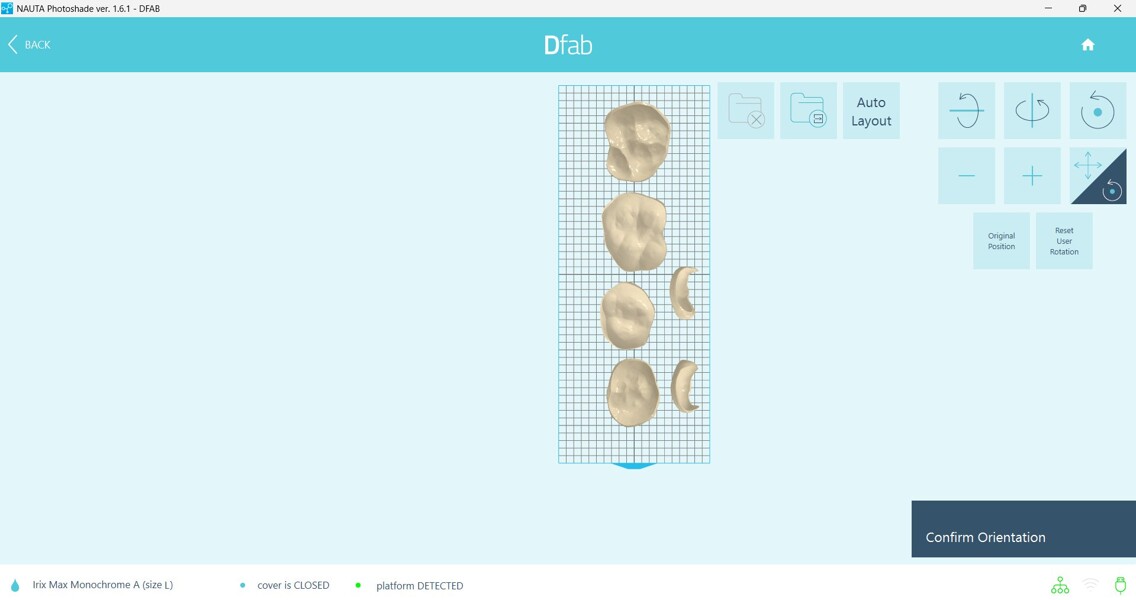

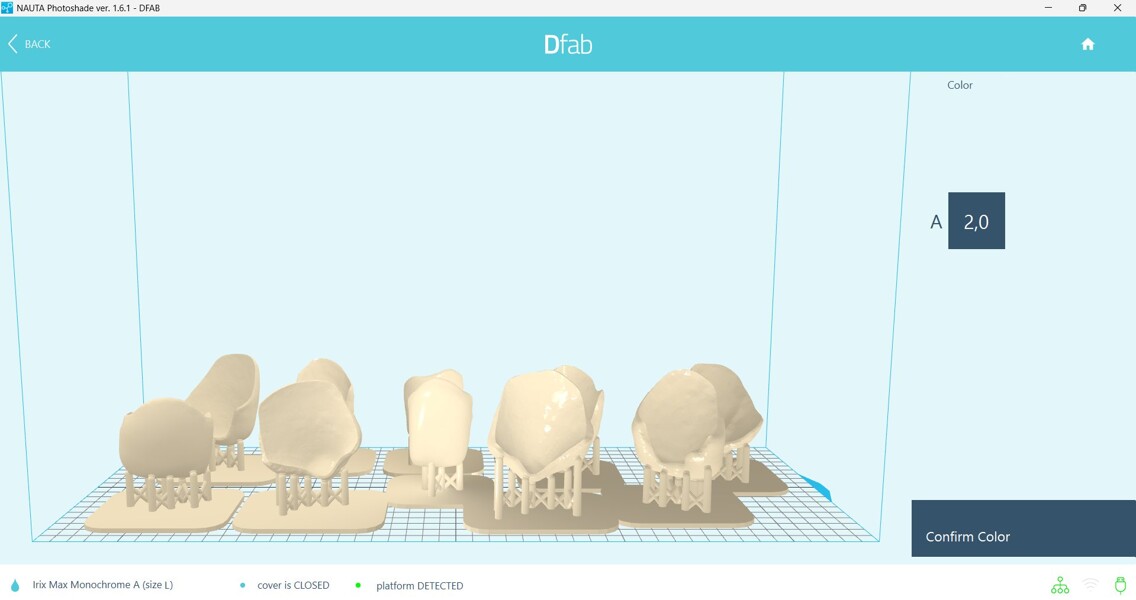

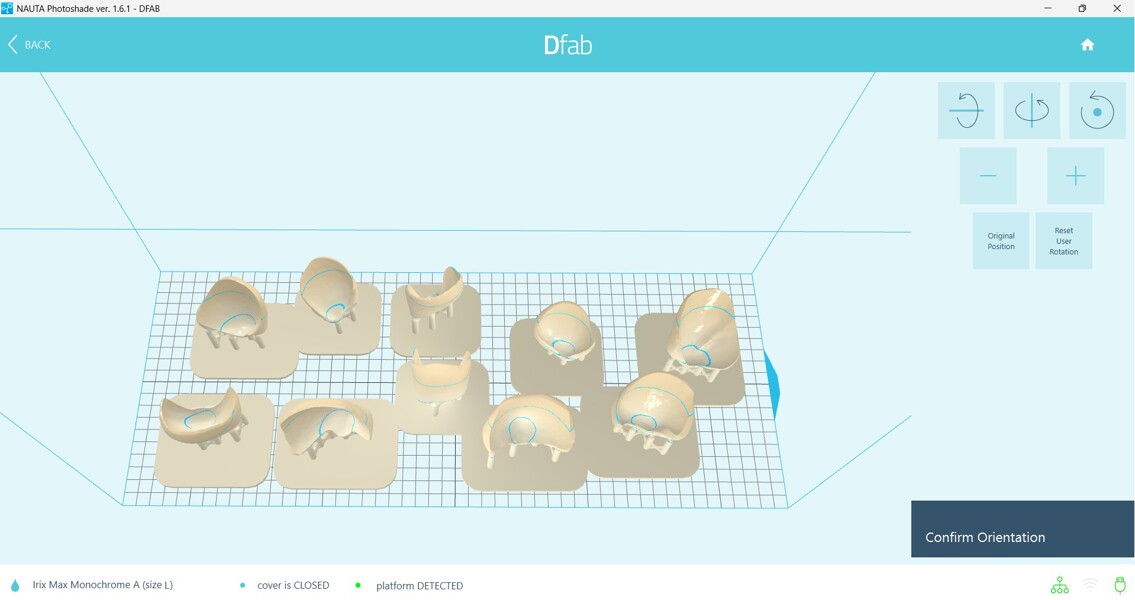

The application of the TSLA 3D-printing technology allowed for the rapid and precise fabrication of monolithic restorations tailored to the unique anatomy of a developing primary dentition. The closed-cartridge system offered significant clinical advantages, such as simplified material handling, reduced cross-contamination risk and improved workflow cleanliness, critical in paediatric settings, where treatment time and patient cooperation are limited. The use of partial restorations also facilitated relative isolation, optimised cementation conditions and enabled predictable removal of excess luting material in a paediatric setting. Previous studies have demonstrated the accuracy and clinical applicability of 3D-printed restorations using composite-based resins, supporting their use in definitive paediatric treatments.1, 6

Overall, this patient treatment supports the clinical viability of 3D-printed composite restorations as a minimally invasive, patient-centred treatment option for children with developmental dental anomalies. However, longitudinal studies are warranted to assess the long-term durability, colour stability and retention of such restorations in the primary dentition.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates the clinical feasibility and effectiveness of using 3D-printed composite restorations for minimally invasive rehabilitation of a young patient with suspected ED. The treatment achieved improvements in aesthetics, speech and function without the need for tooth preparation or local anaesthesia, key considerations in paediatric dentistry. Despite challenges related to isolation, cement removal and polishing in a very young child, the digital workflow, combined with behaviourally adapted management, enabled a predictable and well-tolerated outcome. The 3D-printed composite restorations used represent a promising option for early, patient-centred intervention in cases involving developmental dental anomalies.

Austria / Österreich

Austria / Österreich

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bulgaria / България

Bulgaria / България

Croatia / Hrvatska

Croatia / Hrvatska

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

France / France

France / France

Germany / Deutschland

Germany / Deutschland

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Hungary / Hungary

Hungary / Hungary

Italy / Italia

Italy / Italia

Netherlands / Nederland

Netherlands / Nederland

Nordic / Nordic

Nordic / Nordic

Poland / Polska

Poland / Polska

Portugal / Portugal

Portugal / Portugal

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Slovenia / Slovenija

Slovenia / Slovenija

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Spain / España

Spain / España

Switzerland / Schweiz

Switzerland / Schweiz

Turkey / Türkiye

Turkey / Türkiye

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

Brazil / Brasil

Brazil / Brasil

Canada / Canada

Canada / Canada

Latin America / Latinoamérica

Latin America / Latinoamérica

USA / USA

USA / USA

China / 中国

China / 中国

India / भारत गणराज्य

India / भारत गणराज्य

Pakistan / Pākistān

Pakistan / Pākistān

Vietnam / Việt Nam

Vietnam / Việt Nam

ASEAN / ASEAN

ASEAN / ASEAN

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Middle East / Middle East

Middle East / Middle East

To post a reply please login or register