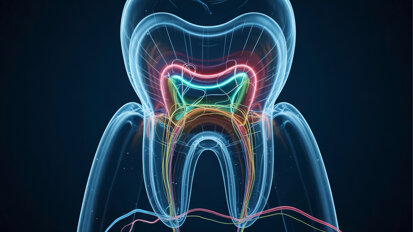

One proposed method to address structurally compromised teeth is crown lengthening, aimed at providing optimal conditions for tooth restoration. However, challenges arise with this approach, particularly in the aesthetic zone, where certain techniques may be limited by their impact on gingival symmetry.2, 3 The diagnostic and planning process for crown lengthening of anterior teeth is notably intricate, necessitating careful consideration to avoid potential asymmetry in gingival margins. Particularly prevalent in the aesthetic zone, notably the maxillary incisors, dentoalveolar trauma often results in the loss of coronal structure.4, 5 In such cases, restoration of the affected tooth may require additional procedures to achieve adequate supragingival height.

Surgical extrusion is a procedure through which the remaining dental structure is repositioned in a more coronal position within the alveolus.6–8 The primary objective of this technique is to elevate the affected tooth to a more coronal position, thereby creating favourable conditions for establishing an adequate ferrule, crucial for facilitating the placement of a restoration that preserves a healthy biological width.3, 7 Consequently, surgical extrusion can be a valuable approach in the treatment of severely damaged teeth, particularly in the aesthetic zone.

Surgical extrusion has various names, including intra-alveolar transplant, intentional reimplantation and forced eruption.6, 9, 10 Although the technique was initially described in 1978,11 the first case report was not published until 2002.12 Despite its early documentation, surgical extrusion remains relatively uncommon in dental practice.

Initially, the periodontal ligament is delicately loosened through syndesmotomy, followed by careful luxation facilitated by periotomes and/or elevators. Using forceps, the tooth is then gradually extruded, typically achieving a vertical displacement of 4–6 mm. To stabilise the tooth in its new position, it is immobilised for a period of two to three weeks with the aid of a flexible splint, followed by placement of a post and core and subsequently a definitive full-coverage restoration. This effective technique can be implemented with relative ease, requiring no specialised surgical expertise. Moreover, it often yields satisfactory aesthetic results, boasts a low failure rate and tends to be well received by patients.

Case series and clinical reports are classified as low-evidence literature because the causal relationships between intervention and outcomes cannot be definitively established without a control group.13, 14 Nonetheless, clinical reports can influence decision-making in dental practice,14 for example by raising awareness of new techniques, clinical approaches and research directions. The objective of this case report is to present a four-year follow-up clinical case in which a compromised anterior tooth was preserved through surgical extrusion.

Case report

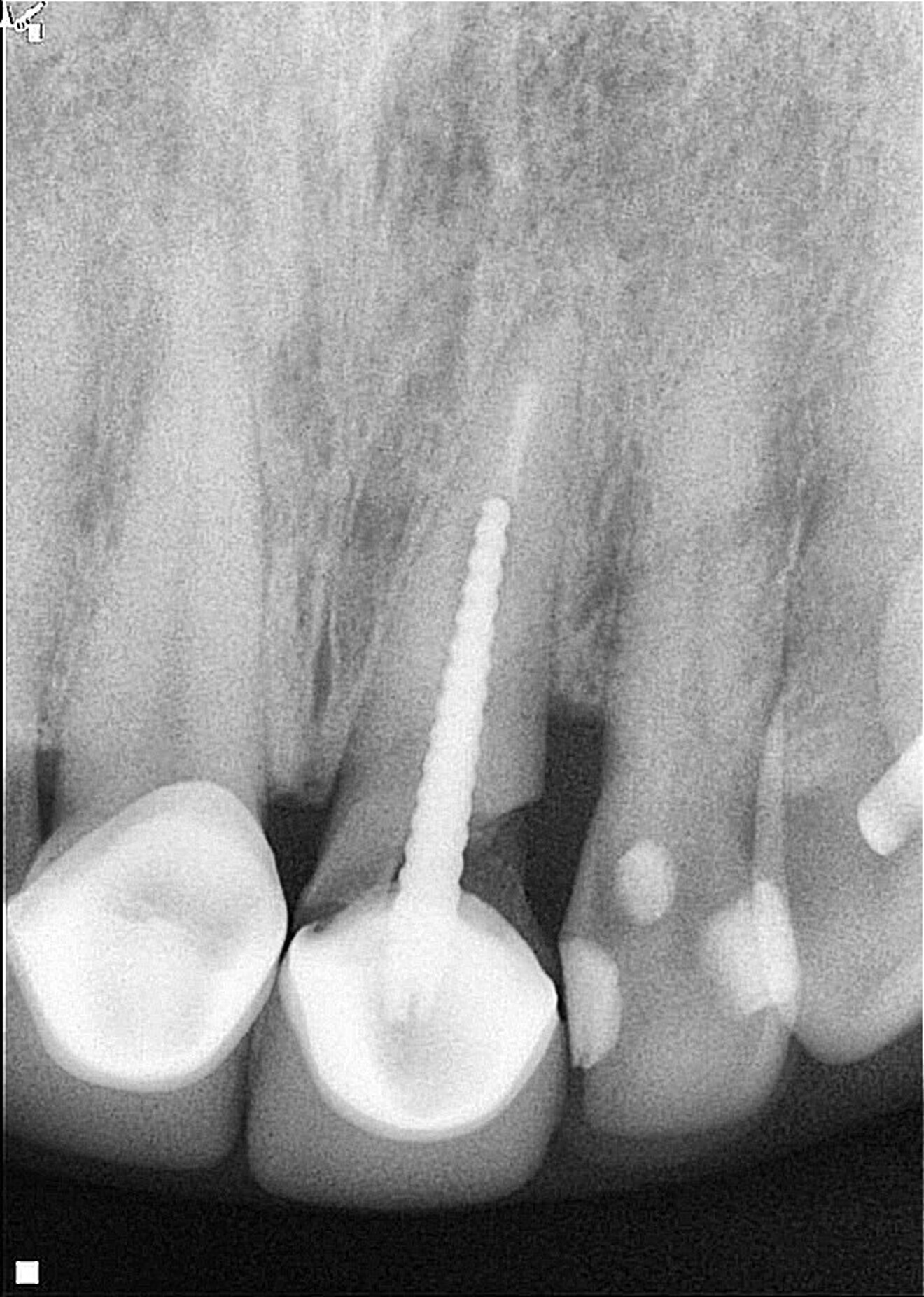

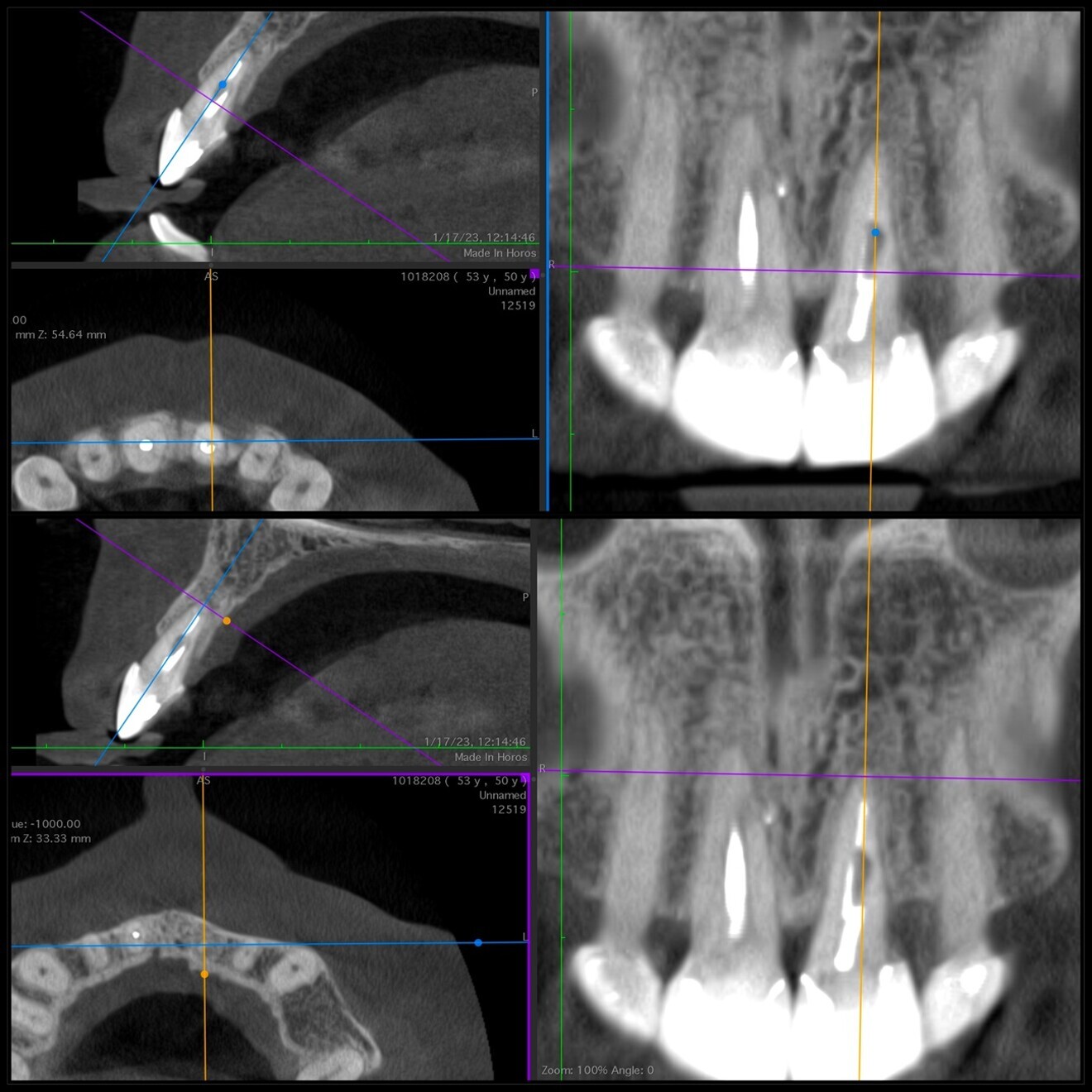

A female patient was evaluated in the dental office after a traumatic event involving her maxillary teeth. She had an oblique fracture from the mesial to distal aspect of the maxillary left central incisor at subgingival level, and the tooth’s metal post and metal–porcelain crown presented with mobility. The tooth had healthy periapical tissue (Fig. 1). Upon radiographic and clinical evaluation, it was noted that there was insufficient dental structure for a predictable restoration.15 Treatment planning included measurement and analysis of the root length, of the width of the root canal walls and of the available supragingival structure. Various treatment options were considered to save the tooth, and after a comprehensive evaluation, surgical extrusion was chosen as the preferred option to achieve adequate healthy supragingival dental structure, thereby offering the patient a favourable long-term treatment solution.6, 8

Austria / Österreich

Austria / Österreich

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bulgaria / България

Bulgaria / България

Croatia / Hrvatska

Croatia / Hrvatska

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

France / France

France / France

Germany / Deutschland

Germany / Deutschland

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Hungary / Hungary

Hungary / Hungary

Italy / Italia

Italy / Italia

Netherlands / Nederland

Netherlands / Nederland

Nordic / Nordic

Nordic / Nordic

Poland / Polska

Poland / Polska

Portugal / Portugal

Portugal / Portugal

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Slovenia / Slovenija

Slovenia / Slovenija

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Spain / España

Spain / España

Switzerland / Schweiz

Switzerland / Schweiz

Turkey / Türkiye

Turkey / Türkiye

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

Brazil / Brasil

Brazil / Brasil

Canada / Canada

Canada / Canada

Latin America / Latinoamérica

Latin America / Latinoamérica

USA / USA

USA / USA

China / 中国

China / 中国

India / भारत गणराज्य

India / भारत गणराज्य

Pakistan / Pākistān

Pakistan / Pākistān

Vietnam / Việt Nam

Vietnam / Việt Nam

ASEAN / ASEAN

ASEAN / ASEAN

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Middle East / Middle East

Middle East / Middle East

To post a reply please login or register